The President appears to be running not so much against Biden as against the pandemic, which is decisively winning

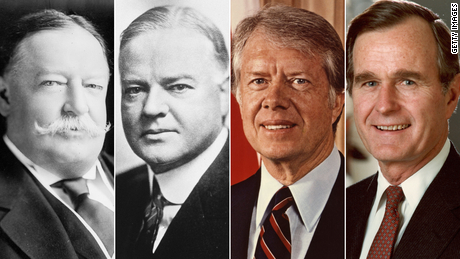

And history underscores the risks for Trump if he cannot shake the negative judgments. While relatively few first-term US presidents have not been reelected, every elected incumbent who has lost since the 20th century began — a list that includes William Howard Taft, Herbert Hoover, Jimmy Carter and George H.W. Bush — lost big. And their resounding defeats were rooted in voters’ convictions that those presidents had failed on the biggest challenges facing America at the time.

Trump’s deficit now “is not something you can tactically maneuver out of,” says Liam Donovan, a Republican consultant. “There has to be some kind of fundamental inflection point that gives people hope or reassurance that some form of normalcy will return.”

Presidents William Howard Taft (from left), Herbert Hoover, Jimmy Carter and George H.W. Bush lost reelection by large margins.

Trump advisers, like aides to every incumbent president facing widespread public discontent, insist they will make the reelection campaign “a choice, not a referendum” by shifting attention from their own performance to the fitness of their opponent. In practice, for incumbents in both parties, that has proved exceedingly difficult to do.

Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, for instance, in their reelection campaigns of 2004 and 2012, respectively, both won about 90% of the voters who approved of their performances and lost a slightly greater share of those who disapproved, according to the exit polls. Voters who “strongly” disapproved of Obama’s performance in 2012 voted 96%-1% against him, while Bush lost those who “strongly” disapproved of him by 97%-2%.

Likewise, President George H.W. Bush won just 5% of the voters who strongly disapproved of his performance in his 1992 loss and President Bill Clinton won only 2% of such voters in his 1996 victory, according to the American National Election Studies surveys. Back in 1980, Jimmy Carter did slightly better, but even so, 9 in 10 of those who strongly disapproved of his performance voted against him in his losing campaign that year, the same surveys found.

Incumbent presidents, these surveys have found, have generally had greater success at holding the more conflicted voters who report they “somewhat” disapprove of their performances: Carter, Clinton, and Bush father and son each won between about one-fifth and one-fourth of those voters, while Obama carried about 1 in 11.

Trying to change the subject

George W. Bush’s reelection in 2004 is considered the most successful recent effort by an incumbent to tilt the campaign’s focus from his own record to the fitness of his challenger, then-Democratic Sen. John Kerry of Massachusetts. Bush’s campaign and his allies tarred Kerry as a flip-flopper who had exaggerated his war record in Vietnam, while painting the incumbent as a resolute “decider” who voters could trust to stand by his convictions even when they didn’t entirely agree with them.

There was a “very limited universe” of voters who disapproved of Bush but might still back him because they liked Kerry less, “which made it a real challenge,” says Mark McKinnon, a senior adviser to Bush’s campaign. “We had to thread the needle.”

Even with that advertising barrage against his rival, the exit polls showed that Bush faced almost complete rejection from voters who strongly disapproved of his own performance. That precedent underscores the challenge facing Trump, because “the vast majority of his disapprovers strongly disapprove of him,” notes Alan Abramowitz, an Emory University political scientist.

Abramowitz recently studied more than two dozen national surveys since early March that asked voters for their assessments of Trump’s overall performance and his handling of other issues, including the economy and the coronavirus outbreak. His conclusion was that voters’ views on Trump’s response to the coronavirus outbreak predicted their verdict on his overall performance far more than any other issue.

“I think fundamentally this race is about the handling of a crisis right now, and he’s not handling it well,” says McKinnon. “That is blotting out the sun on everything else.”

Cracks in Biden’s lead?

“It’s a little bit of a canary in the coal mine,” says McKinnon.

GOP pollster Glen Bolger agrees: “If I were the Biden folks I would be nervous about my image,” he says, particularly because favorability numbers may predict a race’s direction before change is evident in the ballot test.

Still, Democratic pollster Sean McElwee, co-founder and executive director of the liberal group Data for Progress, says that while he believes “Biden is very much in the driver’s seat right now … the most likely scenario for tightening” is that Trump raises the share of voters who are negative toward both candidates and is then “able to claw back with that share of voters.”

McElwee’s answer is that all the groups in the Democratic constellation should be investing less money making the negative case against Trump — “Trump is already being hit by reality, so to speak” — and more on building a positive case for Biden, especially to younger voters of color. “Right now, there are just a lot of voters who [think] Biden is an old white guy that they’ve never heard of,” he says.

Such dismissive perceptions might threaten youth turnout for Biden. But in national surveys, voters unhappy with Trump are still giving Biden big leads, no matter their views of the former vice president. In last week’s Quinnipiac survey, for instance, just 39% of independents said they viewed Biden favorably, yet he drew 51% of their vote and led Trump comfortably. Even more emphatically, the poll showed Biden attracting almost two-thirds of the vote among those aged 18-34, even though only a little over one-third viewed him favorably.

Biden’s vote share against Trump did more closely track his favorability among some groups — including college-educated whites and seniors — but overall the results underscore the conclusion of analysts in both parties such as Donovan, who says flatly: “It’s not going to be a race about Joe Biden. It’s going to be a race about the President and how he is comporting himself down the stretch.”

“If their plan is to convince voters that the pandemic and recession is less important than Fox News boogeymen, it’s a losing strategy,” Schwerin says. “The most important thing Trump could do to improve his standing is to combat the pandemic, and he’s not doing that.”

What history tells us

In both parties, strategists find themselves deeply ambivalent about whether Biden can sustain his outsized lead in surveys. History points them toward different conclusions.

Recent history says no. Because the country is so highly polarized and closely divided between the parties, many tilt toward the assumptioin that the final result will be closer, maybe much closer, than polls now document. No presidential candidate has won by a double-digit margin since Ronald Reagan in 1984.

But the longer history of incumbents defeated for reelection points to the alternative possibility: that the race remains one-sided so long as most voters are dissatisfied with Trump’s performance.

First-time incumbent presidents haven’t lost that often in American history: only five who were renominated did in the 19th century and five more during the 20th century. (No incumbents have yet lost in this century.) The 19th-century defeats sometimes involved relatively small shifts in support: For instance, after Benjamin Harrison narrowly beat President Grover Cleveland in the Electoral College in 1888 (while losing the popular vote), Cleveland came back to narrowly unseat Harrison four years later.

But from the turn of the 20th century, the swings have been much larger in races involving defeated incumbents.

Republican William Howard Taft saw his share of the vote collapse by more than 28 percentage points from 1908 to his astonishingly weak third-place finish behind winner Woodrow Wilson and independent candidate Theodore Roosevelt in 1912. Republican Herbert Hoover lost almost 19 points off his 1928 vote share in his 1932 landslide defeat by Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The vote share of Democrat Jimmy Carter dropped more than 9 points from his 1976 win to his decisive loss to Ronald Reagan in 1980’s three-way race. In 1992, Republican George H.W. Bush’s share of the vote dropped fully 16 points from his 1988 victory, even though Ross Perot’s success at attracting some disaffected voters to his independent candidacy constrained the margin of Bill Clinton’s victory. None of those defeated incumbents attracted more than 41% of the vote, about where Trump is polling today.

The only losing incumbent who kept his race close was Gerald Ford in 1976, and he deserves two asterisks. He’s the only president on this list who was not first elected in his own right (he came to office after Richard Nixon resigned in 1974), and although he finished close to Carter in 1976, Ford’s vote share of 48% still represented a mammoth decline of nearly 13 percentage points from Nixon’s total four years earlier.

The story in the Electoral College is similar. Each of these defeated incumbents experienced a net decline of about 500 Electoral College votes or more: Bush, for instance, went from a 315-vote Electoral College advantage in 1988 to a 202-vote deficit in 1992. Carter went from a 57-vote advantage in 1976 to a 440-vote deficit in 1980. (Taft, Hoover and Ford suffered even greater declines from their party’s tallies four years earlier.)

In today’s highly polarized atmosphere, when partisan attachments are considered much more “sticky” than even a few decades ago, hardly any in either party can imagine such a lopsided result. But if the virus continues to rage, and most Americans continue to believe Trump has mishandled it, he could find himself in the uncomfortable company of Oval Office predecessors who also faced public judgments that they failed — and then paid a massive electoral price.

![]()