Analysis: Bumpy road ahead for Biden’s infrastructure plan

Infrastructure was a road to nowhere for former presidents Donald Trump and Barack Obama. But Joe Biden believes he can use it to drive America to the future after a dozen years of false starts.

The trip is unlikely to be smooth.

Biden’s $2.3 trillion infrastructure package, released Wednesday, would go well beyond the usual commitments to roads and bridges to touch almost every part of the country. It’s a down payment on combating climate change, a chance to take on racial inequities, an expansion of broadband, an investment in manufacturing and a reorienting of corporate taxes to pay for everything. To succeed where his predecessors stalled, Biden will have to navigate a conflicting set of political forces with winners and losers all around.

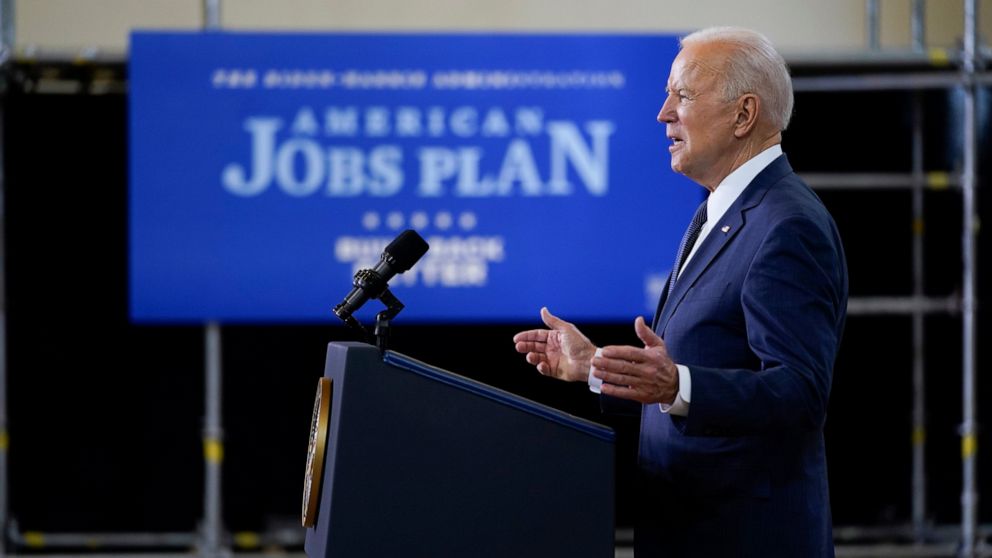

“It’s big, yes, it’s bold, yes, and we can get it done,” the president said in a Wednesday afternoon speech in Pittsburgh. “In 50 years, people are gonna look back and say, this was the moment that America won the future.”

Biden sees infrastructure as a fundamental promise that must be honored before Democrats face voters in 2022.

The president resisted calls by business groups to pay for his plan with higher gas taxes and tolls, since the costs would be borne by working Americans and Biden had promised no tax hikes on anyone making less than $400,000. That’s according to an administration official who insisted on anonymity to discuss private conversations.

Yet the decision to keep that particular promise likely dooms any chance of wider bipartisan unity.

Biden’s proposal would gut the core of Trump’s 2017 tax cuts — an affront to many Republican lawmakers, who would also prefer that infrastructure stay in a narrow lane. The corporate tax rate would jump to 28% from 21% under Biden’s plan, and a global minimum tax would be charged to prevent companies from avoiding taxes.

Even before Biden delivered his opening speech on the plan, Republicans had latched on to Reagan-era labeling, dismissing the package as tax-and-spend liberalism. That’s an attack designed to erode public support as different components of the package get divvied up among congressional committees and begin their journey through Congress.

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky called the plan a “Trojan horse” for tax hikes. Trump issued a statement saying the big winner would be China because U.S. jobs would move overseas due to higher taxes.

“It is the exact OPPOSITE of putting America First—it is putting America LAST!” said Trump, whose own repeated attempts at an “infrastructure week” failed to capture political momentum and became something of a punchline.

Some Democratic lawmakers, on the other hand, fear Biden’s plan does too little over eight years. Others see it as a chance to tinker by repealing the $10,000 taxpayer limit on deducting state and local taxes, or SALT, that was instituted under Trump. Each possible Democratic defection matters because vacant seats leave House Democrats with the thinnest of majorities. And in the evenly split Senate, Democrats must rely on Vice President Kamala Harris’ tie-breaking vote for their edge.

“I can only vote for a bill that has meaningful tax impact for my constituents if it addresses the SALT cap,” tweeted Rep. Tom Malinowski, D-N.J., one of four lawmakers demanding to expand deductions.

Some environmentalists, meanwhile, say the plan doesn’t do enough to stop the tides of climate change, even with its proposed upgrades to the power grid and plans to build 500,000 electric-vehicle charging stations. They could push Biden to go even bigger, though he plans to announce a second package in the coming weeks focused on child care, family tax credits and other domestic programs, paid for by tax hikes on wealthy individuals and families.

Rep. Pramila Jayapal, D-Wash., chair of the near-100-member Congressional Progressive Caucus, said climate change demands that Biden commit to more money.

“It makes little sense to narrow his previous ambition on infrastructure or compromise with the physical realities of climate change,” she said.

Almost every trade group in Washington representing interests from semiconductors to steel has a stake in the infrastructure bill, as does organized labor, which sees the potential for union jobs.

Business groups have long backed bold investment in infrastructure — just not through taxes on their members. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and Business Roundtable — major players in terms of donations — both strongly oppose the tax hikes.

White House officials welcome the coming debate as a way to press their case, using the same kind of strategy that Biden deployed with his $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief that became law in March. If tax hikes are opposed, how should the infrastructure be financed? What are lawmakers’ counteroffers?

The difference in this proposal, compared to coronavirus relief, is that infrastructure is not an emergency that can be funded through debt with minimal tradeoffs. Instead, congressional committees can break up its details and consider each of them separately, possibly peeling off elements like highway or water infrastructure that have some bipartisan support. In fact, past failures mean that many of the ideas being proposed have circulated among lawmakers for decades.

But failure by political leaders this time could be devastating for America’s economic trajectory. Once the economy bounces back from the pandemic, economists expect growth to fade below the relatively sluggish levels of the Obama and Trump eras. Infrastructure is a central way to increase worker productivity, the ultimate source of wealth and productivity.

“It’s the first time that I see a comprehensive plan that truly can have a fundamental change in American productivity,” said Sadek Wahba, founder of the infrastructure investment firm I Squared Capital. “This is really the moment. If we’re not able to do it now, I would be very, very pessimistic about our ability to maintain our productivity over the coming decade.”

———

AP writers Lisa Mascaro and Kevin Freking contributed to this analysis.

———

EDITOR’S NOTE: Josh Boak has covered the U.S. economy and the White House for The Associated Press for seven years.

![]()