Faulty ballots and frustration: Texans confront ‘nightmare’ effects of new election law as early voting kicks off

This year, the 74-year-old printed the application on January 3, filled it out and mailed it to her local election office. Days later, a rejection letter arrived: The forms she had pulled from the county’s website no longer complied with Texas law.

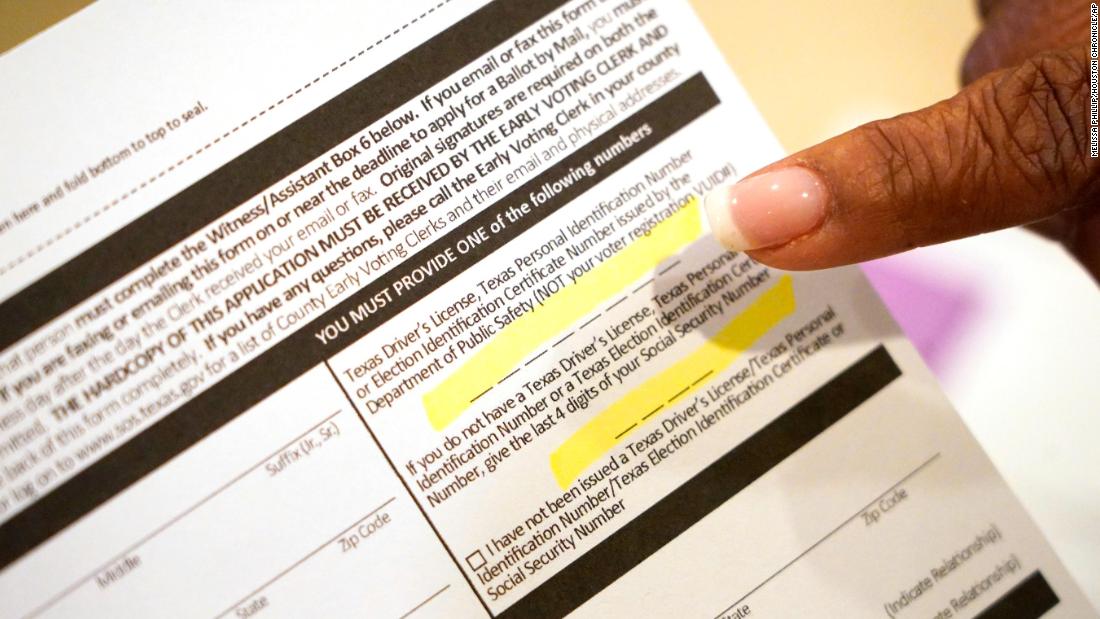

So, she tried again — using the new form, which required her to submit a Texas identification number or partial Social Security number. But it, too, was rejected. The problem this time: She had submitted her driver’s license number, but it didn’t match the identification she used 46 years ago when she first registered to vote after moving to Fort Bend County.

“I am mad as hell,” said Gaskin, who grew up watching her father pay poll taxes for himself and other African Americans in Galveston County so they could vote. “These are the things we fought 60 years ago, 50 years ago, and we are still fighting them. And that is not right.”

At stake: primary races for governor and six other statewide offices, along with contests for state legislative and congressional seats and other local positions. Early, in-person voting runs through February 25. The final day of voting in the primary is March 1.

In addition to the new ID requirements to vote absentee, the law makes it a crime for a public official to mail out absentee ballot applications to voters who haven’t requested them. SB1, as the law is known, also takes aim at Harris County — home to Houston — which offered 24-hour voting during the pandemic in 2020. The law limits early voting hours and bans drive-thru voting, another tool the county used.

The changes already have resulted in higher-than-usual rejection rates for absentee ballot applications. And some counties have begun to report new problems: Hundreds of mailed ballots flagged for rejection over ID requirements.

Voters also have to include a Texas identification number or a partial Social Security number when returning their mail-in ballots — despite having already provided similar identifying information when they applied for the ballot in the first place. If they have neither number, they must also indicate that.

In the Democratic stronghold of Harris County, 40% of mailed ballots received by election officials through late last week had been flagged for problems. Virtually all were missing identification.

“It’s my job, literally, to help voters, to advise them, to encourage them to vote,” Longoria told CNN in a recent interview, citing her frustrations with the law.

‘Everything that can go wrong … has been going wrong’

Texas is one of 19 states that passed new voting restrictions in 2021, according to a tally by the liberal-leaning Brennan Center for Justice at New York University’s school of law. Largely Republican-controlled legislatures last year raced to establish new voting rules amid false claims by President Donald Trump that widespread voter fraud contributed to his election loss in 2020.

“Basically, everything that can go wrong with this has been going wrong,” said James Slattery, a senior staff attorney with the Texas Civil Rights Project, said of the implementation of the Texas law. He worries other states are “going to go through this type of ordeal when their time eventually comes.”

Grace Chimene, the president of the League of Women Voters of Texas, said the “past three, four weeks have been a nightmare” for voters.

“We tried to tell (lawmakers) during the legislative session that this was going to be a nightmare,” she added, “and they went ahead and just passed this.”

Sen. Bryan Hughes, the leading Republican behind the measure, and his spokesman did not respond to interview requests. Last year, Hughes cast the changes as needed to secure elections.

“The right to vote is too precious, it costs too much, for us to leave it unprotected, unsecured,” he said at the time.

Officials with the Texas secretary of state’s office say a unique set of circumstance have led to the current mess.

‘A blood-bought right’

Local officials are hoping that rejection rates will fall as they scramble to answer voters’ questions and help them correct mistakes.

In Harris County, the state’s most populous, Longoria said she’s doubled the call center staff to help answer questions.

Only a narrow slice of the population can legally vote by mail in Texas. Among them: Those 65 and older, people who are sick or disabled, and those who will be out of their home county during in-person voting.

In all, nearly 1 million Texans voted by mail in 2020, out of 11.3 million votes cast.

Gaskin, a longtime member of the League of Women Voters and the daughter of civil rights activists, calls voting “a blood-bought right.” And she remembers when it wasn’t guaranteed for all.

Congress had just passed the Voting Rights Act in August 1965 when she entered college. And as a student, she helped register Black voters in Austin, Texas — some of whom were voting for the first time, Gaskin said.

She still helps register other voters and rarely misses an election herself. She and her husband, who has Parkinson’s disease, have voted by mail for years. So she was stunned by how hard it was to navigate voting this year.

“I have a degree in English from the University of Texas at Austin,” she said. “I know how to read and follow directions, and I’m determined. I’m convinced that a lot of people who get these rejection letters will just give up.”

On the third try, Gaskin properly completed the application. She and her husband received their ballots on January 31, nearly a month after she started the process.

(She had to fill out extra paperwork to assist her husband with his ballot, including checking a box to confirm that she was not compensated in any way to help him cast his ballot — another new requirement of the Texas law.)

Gaskin said she now has a new mission in the weeks ahead: “I have to track my ballot and make sure it gets counted.”

![]()