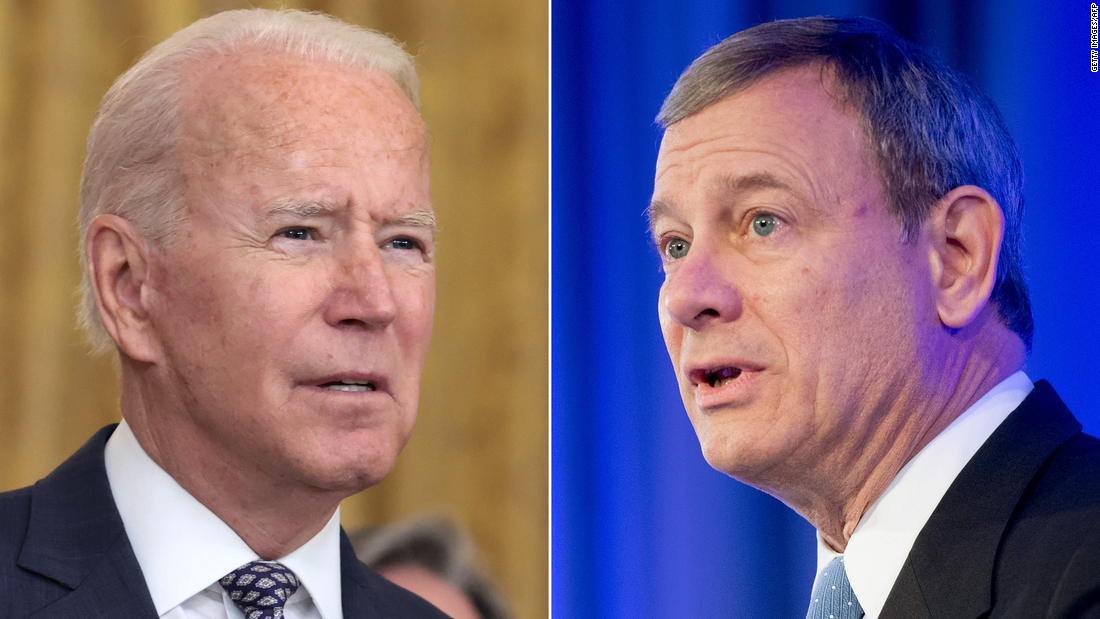

Conservative-dominated bench denies Biden same deference it once gave Trump

The Biden administration is facing multiple legal challenges in lower courts to its immigration, economic and environmental policy changes. The federal judiciary, led by the Supreme Court, could stall a significant part of the President’s agenda.

The temporary freeze on evictions was originally imposed by Congress and expired at the end of July, but after public outcry, the White House and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention extended the freeze. The current measure was intended to cover counties with high rates of Covid-19 transmission through October 3.

“COVID-19 transmission rates have spiked in recent weeks,” Breyer observed, “reaching levels that the CDC puts as high as last winter: 150,000 new cases per day. … The public interest strongly favors respecting the CDC’s judgment at this moment, when over 90% of counties are experiencing high transmission rates.”

An estimated 11.4 million American adults are behind on their rent, and Congress has appropriated about $46 billion to help renters and landlords.

Earlier this week, the three liberals protested the majority’s action refusal to block a lower court order that compels the Biden administration to revive the Trump-era “Remain in Mexico” policy for migrants seeking US asylum.

That order, which followed a strict court timetable for filings in the case and was issued less than an hour after the Biden legal team’s reply came in, denied the administration the usual judicial deference for such immigration cases.

The ruling reinforced lower court judges’ view that the Biden dissolution of the Trump-era screening for US asylum seekers at the southern border was arbitrarily imposed, in violation of federal procedural law.

Fight will escalate this fall

In some respects, conflict between a liberal Democratic administration and GOP-controlled court are predictable, especially with three Trump nominees and a conservative supermajority.

But Roberts, an appointee of Republican George W. Bush, has stressed that the justices are not politically motivated. And other justices, including Breyer, have echoed such assertions in academic settings.

When it comes to deciding significant cases, however, they often split along such political and ideological lines. In major disputes from last session, the justices sided with Trump lawyers over the newly installed Biden ones.

As this week’s controversies demonstrated, the two sides clash not only on the substance of the law but what procedures — time and briefing schedules — should be afforded.

Dissenters insisted on Thursday that administration lawyers were raising “contested legal questions about an important federal statute on which the lower courts are split and on which this Court has never actually spoken. These questions call for considered decisionmaking, informed by full briefing and argument. Their answers impact the health of millions. We should not set aside the CDC’s eviction moratorium in this summary proceeding.”

The case picked up from a June 29 Supreme Court ruling allowing the eviction freeze to remain in place but with a caveat from Kavanaugh, who cast the crucial fifth vote preserving the prior moratorium. He said he was doing so only because it was set to expire on July 31.

The intervening weeks, he said, “will allow for additional and more orderly distribution of the congressionally appropriated rental assistance funds. … In my view, clear and specific congressional authorization (via new legislation) would be necessary for the CDC to extend the moratorium past July 31.”

The other justices did not explain their positions for or against that moratorium.

This time around, the conservatives who prevailed emphasized their “careful review of the record” as they said the 1944 federal public health law at the core of the dispute should be narrowly construed. They referred to it as “a decades-old statute … to implement measures like fumigation and pest extermination.”

Dissenting justices took issue with that narrow interpretation, saying Congress’ early public health law included eviction moratoria and that if Congress had wanted to exclude such measures in later law it would have said so.

More pointedly, dissenters said that the court had failed to sufficiently explain the legal ramifications on the first go-round.

For the broader public health consequences facing the Biden administration and all Americans, they noted that predictions about the course of Covid-19 “have proved tragically untrue. Today they show just how little we may presume to know about the course of this pandemic.”

![]()