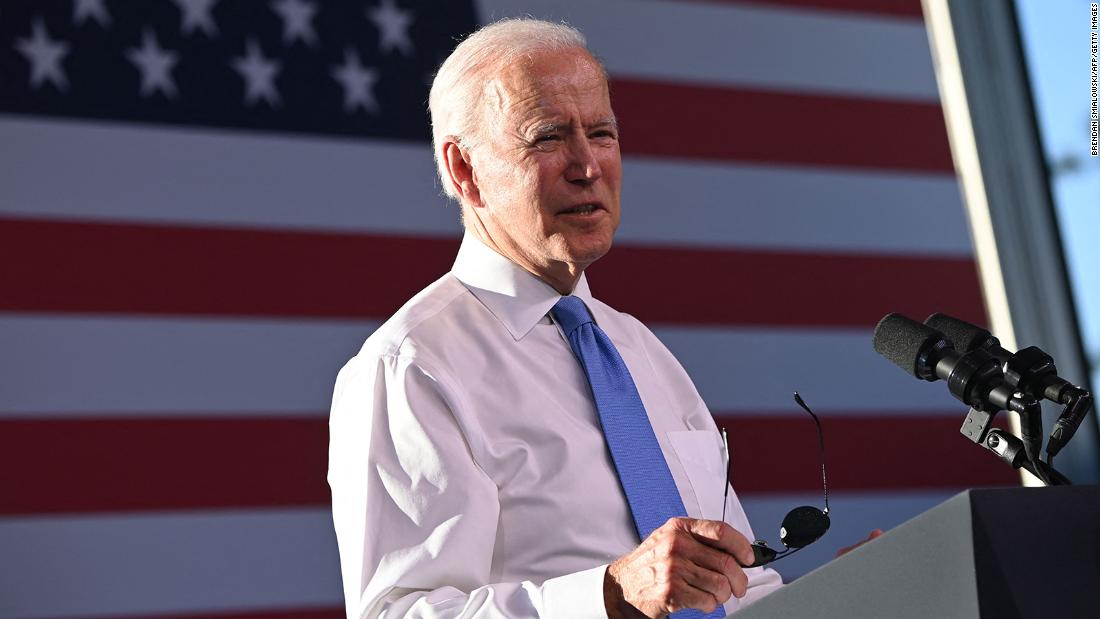

Analysis: After showdown abroad, Biden faces one at home

After successfully enacting a massive Covid-19 rescue bill and rolling out an unprecedented vaccination drive, the President is now under increasing pressure to satisfy Democratic hopes of transformative reform in a fast narrowing window for action.

To pass an infrastructure bill for instance, the President will first have to secure a deal among 20 bipartisan senators now looking for common ground. Any deal will be well short of the original $2 trillion bill he had originally envisaged and will center on traditional projects like roads and bridges while removing controversial social spending he had packed into his original blueprint. Another issue is how to pay for the package, with Republicans refusing to scale back tax cuts introduced in the 2017 law passed by then-President Donald Trump.

Progressives demand action on their priorities

Complicating Biden’s challenge, progressive Democrats are skeptical that any Senate compromise will satisfy their priorities. And they warn that they would not agree to such a pared back compromise without a commitment to pass items like home health care and climate change mitigation measures, which were in the original infrastructure bill, through the Senate by using a simple majority device used for budget legislation known as reconciliation.

“We’ve already wasted three weeks of bipartisan negotiations only for them to lead nowhere,” Congressional Progressive Caucus Chair Pramila Jayapal of Washington told reporters on a press call.

“I have been saying for weeks that we are not going to be able to get the votes for a smaller package unless there is simultaneous movement of an agreed-upon reconciliation package that includes everything.”

Democratic Sens. Ed Markey of Massachusetts and Jeff Merkley of Oregon similarly said this week that they will not support a bipartisan infrastructure package unless they have a guarantee that climate action will be included in a separate reconciliation package.

Markey said “it’s time” to move beyond bipartisan infrastructure negotiations and for Democrats to “go our own way.” He underscored the urgency of getting something done before the August recess, a key deadline that is looming for Biden.

“We shouldn’t leave here until we get it done. We cannot let Republican calls for bipartisanship deny the American people the climate action that they have been demanding,” he said. “There has to be a guarantee, an absolute unbreakable guarantee that climate is going to be at the center of any infrastructure deal which we cut.”

Schumer emerged from a meeting with Democrats on the Senate Budget Committee Wednesday night calling it a “great first discussion.” Sen. Tim Kaine of Virginia said the first votes could come in July and that the group discussed including climate and immigration provisions.

Kaine acknowledged that it will be difficult to build consensus among all 50 Democrats: “You can’t say we’re unified because we haven’t discussed all the details and there are 50 people.”

Biden appeared to indicate, however, that he believes that a two-track process could unlock both a new infrastructure bill as well as progressive goals.

Biden hopes to bring ‘bookends’ together

“I know that Schumer and Nancy have moved forward on a reconciliation provision as well. So I’m still hoping we could put together the two bookends here,” the President said in Geneva, also referring to Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

A small group of Democrats senators also met with White House officials to brief them on the bipartisan framework for the infrastructure plan, and Manchin said the group hoped to release more details next week.

Steven J. Ricchetti, a counselor to Biden, said the discussion was “very cordial and productive.” But Virginia Sen. Mark Warner said the group is trying to navigate “lots of preconditions from our Republican friends” as well as those of the President, “so it makes it challenging.”

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell previewed the challenges in winning GOP support on Tuesday when he laid out his requirements for a deal: “Put me down as listening and hopeful that somehow, some way, we’ll be able to move forward with an infrastructure bill that does two things.”

McConnell has a choice to make. There are a number of Republicans who want an infrastructure deal to show their constituents they can get something done ahead of midterm elections. But given that a compromise would be a huge accomplishment for a President who has made unity and bipartisanship an unlikely theme of his administration in fraught partisan times, Republicans may ultimately be unwilling to give Biden the win.

McConnell has always been ‘No’

Throughout the early months of Biden’s presidency, Democrats have maintained a fragile peace within their fractured party even as progressives clamor for Biden to go bigger and bolder in tackling the climate crisis and addressing income inequality, which he attempted to do in part with some of his proposals to improve the lot of home health care workers in the broad, initial infrastructure bill

Still, signs of optimism in an institution as polarized as Congress are often only the prelude to disappointment. And given the narrowing window for Biden to capitalize on the apex of his power and influence with midterm elections looming next year, and with only a few weeks before lawmakers go home for the summer, the pieces need to come together soon.

Republicans are looking ahead to the 2022 elections, promising a blockade of Biden’s agenda. Wyoming GOP Sen. John Barrasso noted at an event this week that McConnell came under criticism during Barack Obama’s presidency by saying that he wanted to make sure Obama was “a one-term president.”

“I want to make Joe Biden a one-half-term president,” Barrasso said in an appearance before The Ripon Society. “And I want to do that by making sure they no longer have House, Senate, White House.”

Biden’s dwindling moment for fundamental reform was also underscored this week when McConnell refused to guarantee that he would confirm a Supreme Court nominee if the GOP wins back control of the US Senate.

When the President was asked about McConnell’s comments during his foreign trip, his answer encapsulated the shadow that Republican obstruction cast over his entire agenda.

“Mitch has been nothing but ‘No’ for a long time and I’m sure he means exactly what he says, but we’ll see.”

![]()