The wartime exploits of cabaret star Josephine Baker who smuggled Nazi secrets in her UNDERWEAR

Revealed: The daring wartime exploits of erotic cabaret star Josephine Baker who smuggled Nazi secrets to Winston Churchill in her UNDERWEAR

The black American singer and dancer became a French spy in World War TwoShe sang to concentration camp survivors but insisted: ‘I’m a soldier too’Her music score sheets held secrets in invisible ink handed to London spiesShe was awarded the Medal of the Resistance and the Croix de Guerre

<!–

<!–

<!–<!–

<!–

(function (src, d, tag){

var s = d.createElement(tag), prev = d.getElementsByTagName(tag)[0];

s.src = src;

prev.parentNode.insertBefore(s, prev);

}(“https://www.dailymail.co.uk/static/gunther/1.17.0/async_bundle–.js”, document, “script”));

<!–

DM.loadCSS(“https://www.dailymail.co.uk/static/gunther/gunther-2159/video_bundle–.css”);

<!–

Josephine Baker stepped down from the train carriage, resplendent in her furs: every inch a superstar. She swept along the platform of Canfranc Estacion, the border crossing into Spain from France, giving directions for the unloading and reloading of her luggage. The effect was electrifying.

French and Spanish policemen and customs officers stopped dead. Railway workers gasped in star-struck amazement before dashing to call wives and daughters. They crowded around Josephine, desperate to see, to feel, to touch, to bask in the radiance of that famous smile.

The awe-struck officials barely glanced at the mountain of luggage she’d brought with her: piles of trunks carrying hidden, secret contents that might change the course of the war.

It was 1940 and Josephine was among the world’s most famous women. As a black American singer and dancer facing segregation in her home country, she had emigrated to France in the early 1920s, only 19, seeking fame and fortune.

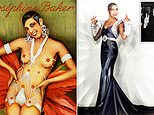

Exotic: Josephine in a Swedish movie poster for her 1927 film Siren Of The Tropics

And she would find these things in France, becoming a global star of stage, screen and song. Josephine set Paris alight with her sexually charged, ‘exotic’, semi-naked dance routines, which scandalised, provoked and captivated her audiences.

The prevailing image of this icon was of her stalking the Paris streets, together with her cheetah, Chiquita, held on a diamond-studded leash.

However, as the years progressed and her fame mushroomed – she was reputedly the most photographed woman in the world by the late 1920s – she was taken more seriously. She gained not just superstar status but fabulous riches, courted by the wealthy, the famous and royalty alike.

She was also known as an outspoken opponent of Nazi Germany. Believing freedom must be fought for every day, she became a spirited and brave supporter of the Allied troops.

Yet there was another, rather less public side to the star which few of her fans would ever have suspected. For, as war approached, Josephine had been recruited as an Honourable Correspondent – an unpaid, freelance intelligence agent for the French secret services. Or, in plain terms, a spy.

Today, thanks to the recent release of some of the most important Second World War-era files concerning her service, the full story of her exploits can be told.

The stakes could hardly have been higher on the mission that took her to the Spanish border in the autumn of 1940, for example.

The objective had been to travel down through the Iberian peninsula to neutral Portugal and its capital, Lisbon. There, she would deliver a consignment of sensitive intelligence material to British representatives.

She was accompanied on the mission by a French spy called Captain Jacques Abtey from the Deuxieme Bureau, the French equivalent of the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS).

The cover story was simple: the famous Josephine Baker was going on an international tour, which would take her first to Lisbon.

American-born French dancer, singer, and actress Josephine Baker pictured circa 1950

Any performer of her standing would naturally travel with voluminous luggage stuffed with tour costumes, make-up and musical scores – bags and boxes perfect for concealing intelligence material, of course. Her score sheets contained not only musical notes but secrets. Abtey had transcribed the most sensitive material on to the pages with invisible ink. Some documents were of such exceptional value that they had to be carried exactly as they were, in their original form. The risks were obvious.

As just one example, the Deuxieme Bureau had given her a ‘series of photographs of landing craft that the Germans are planning to use’ in the invasion of Great Britain, a plan that had been codenamed Unternehmen Seelowe (Operation Sea Lion), material of the greatest possible importance.

Why Lisbon? Like Spain, Portugal was neutral – but was not, like its neighbour, under the sway of fascists. And with the outbreak of war, Lisbon became the espionage capital of the world, awash with agents from all the great powers.

For a spy, Josephine was remarkably conspicuous, although her fame would prove a protection as well as a risk. No sooner had she arrived in the Portuguese capital than she became the story of the moment. Was she staying long? What had brought her there, in the midst of war?

‘I come to dance, to sing,’ she told journalists. ‘I am stopping in Lisbon before going to Rio, where I have further engagements.’

Abtey, meanwhile, ensured that Josephine’s precious scores – covered with invisible writing – plus the reams of original documents and photos were passed to British intelligence through a figure known as ‘Major Bacon’. London was ‘delighted’ to have received such a rich haul of intelligence.

Sir Winston Churchill giving his famous victory sign on an election tour in Glasgow

This mission to Portugal was the first of many taken by the pair using her performances as a cover. On occasion, Josephine travelled solo. Although both were married already, the two agents soon became lovers.

Back in France, however, the dangers were growing. Already a figure of suspicion, Josephine learned she was on the German blacklist and in danger of arrest, imprisonment or worse.

In 1941, Abtey and Josephine fled for North Africa, eventually settling in neutral Morocco. There, they would begin working with the so-called ’12 Apostles’, Washington’s first overseas spies in the Second World War, the pioneers of what would become America’s fledgling foreign intelligence agency, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), itself the forerunner of the CIA. And their missions continued, as did the supply of espionage material from the Deuxieme Bureau.

Josephine travelled to Spain and Portugal on numerous occasions, performing, socialising and carrying dossiers, which were then spirited out to London and the desk of Prime Minister Winston Churchill. One of her contacts was no less a figure than Nicolas Franco, brother of Spain’s fascist leader General Francisco Franco.

Apparently quaffing flutes of champagne and twirling on the dancefloor, Josephine remained all-ears as diplomats and spies from the Axis powers tried to impress her with gossip.

At key moments, she would retire to the ladies’ room, scribbling snippets of information along her arms and even on the palms of her hands. No one would ever suspect a glittering star of such subterfuge.

After each rendezvous, she returned to her hotel and made careful notes of all that she had learned.

Their discovery would have been a catastrophe for her. So she decided to conceal the intelligence she gathered where no one would ever dare to look.

No longer content with snippets of information scribbled on hands and arms, she hid the notes on scraps of paper pinned in her underclothes.

She travelled the world as a performer whilst mining for intelligence from those in the audience (pictured) Ms Baker during her Ziegfeld Follies performance of ‘The Conga’ on the Winter Garden Theater stage in New York, Feb. 11, 1936

Back at her Moroccan base, however, Josephine fell ill. An ache in her stomach escalated into excruciating cramps. She was suffering from peritonitis – inflammation of the abdomen – and over the coming year she almost died several times, her fever suddenly spiking again just as she was starting to recover. Ahead lay months of suffering, during which Abtey would fear that Josephine would ‘collapse under blows that were impossible to parry’.

However, even as she lay in bed in a Casablanca clinic, perilously weak, she and Abtey started to realise something rather startling: perhaps there was a way to turn her illness to their benefit.

Abtey, in particular, had noticed how the clinic offered the perfect clandestine rendezvous point. What, after all, could be more natural than assorted American officials paying a call on this US-born star of stage and screen? Equally, the private confines of a clinic provided the perfect setting to talk, no matter how sensitive the subject matter might be. There were few guards, cooks or secretaries within earshot. As for the medical staff, they were respectful and discreet, announcing their arrival long before they might barge in.

The clinic could even double as a dead-letter drop, a place at which Abtey might leave a dossier in the custody of a bedridden Josephine, for a visitor to collect.

There was another benefit to having Josephine ensconced in her sickbay: safety. World-famous, instantly recognisable, there was no way in which she could adopt any kind of cover, other than to be herself and to hide her espionage in plain sight.

But in Morocco and further afield, her anti-Nazi sympathies were becoming more and more evident.

The war hero is buried in the crypt of the Pantheon, a monument in Paris reserved for National Heroes. Fewer than 100 people – and only five women – have been awarded such a high distinction (pictured) Josephine Baker performs in her last concert entitled ‘Josephine’ at Bobino Theater in Paris. She died aged 69 after the 14th performance from a cerebral hemorrhage at 5 a.m. on April 12, 1975

Her enemies were circling. They knew what Josephine was about. Her outspoken stance coupled with her clandestine work had created powerful foes. Indeed, the German and Vichy French agents had uncovered the true role of Josephine’s Casablanca’s clinic room.

Yet, despite their attempts at surveillance, the clandestine meetings continued behind her shuttered windows. Who could target an ailing star on her sickbed? Even so, when Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa, began in 1942, Josephine, despite remaining weak and vulnerable, insisted on taking to the streets. ‘This hour is too beautiful for me to live it confined within four walls,’ she said.

It was only the following year that she was finally on the road to recovery, and that was when Sidney Williams, the first black director of the American Red Cross, sought her out. Williams was charged with establishing a Liberty Club in Morocco, a Red Cross cafe-cum-social-club where US servicemen could have quality downtime. The American armed forces were heavily segregated, with black soldiers mostly barred from frontline roles.

But Williams was determined to open a club where black and white GIs could mix freely, one of the first of its kind. He was desperate for Josephine to headline the opening night in Marrakech.

As the last lines of her song J’ai Deux Amours faded away and the American Army band accompanying her fell silent, a hush settled over the auditorium. Many had been moved to silent tears. Moments later, the cheers and whoops erupted as the audience rose to its feet.

She began a tour performing for the hundreds of thousands of Allied troops stationed in Algeria. Josephine stipulated one condition: there would be no segregation. Black and white would mix freely.

What was the point in waging war on Hitler, if segregation overshadowed the Allied war effort?

Over the winter of 1944-45, Josephine returned to her frontline duties with a vengeance. From Belfort, Mulhouse, Colmar, Strasbourg and Nancy, she followed the foremost units as they punched across the Rhine and into Germany itself, to Karlsruhe, Stuttgart, Hamburg.

Josephine Baker right, as a volunteer in the Free French Women’s Air Auxiliary circa 1940

Everywhere she went she eschewed special treatment, declaring: ‘I’m a soldier too.’ She even performed for the sick and the dying of the newly liberated Buchenwald concentration camp in east-central Germany. The terrible things she saw would underscore the righteousness of all that she had been fighting for.

She sang for them, her voice low and lilting, suffused with raw emotion. All around her, faces lit up with smiles.

For her wartime service, Josephine would be awarded the Medal of the Resistance with Rosette, the Croix de Guerre, and she would be appointed a Chevalier of the Legion d’Honneur. She would eventually be interred in the crypt of the Pantheon, a foremost monument in Paris reserved as a resting place for those considered the nation’s foremost National Heroes.

Fewer than 100 individuals – and only five women – have been awarded such a high distinction.

![]()