Can California legally require women on corporate boards?

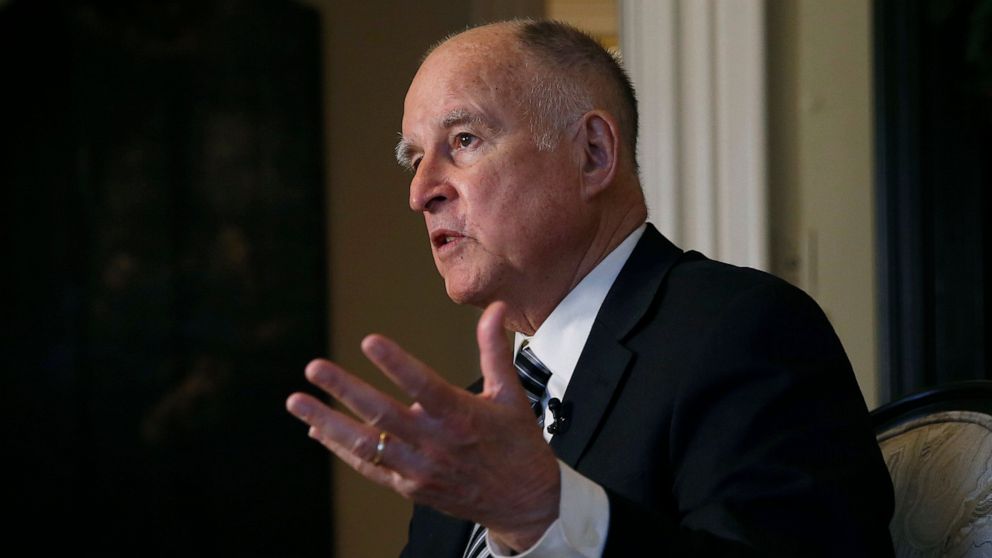

LOS ANGELES — When then-California Gov. Jerry Brown signed the nation’s first law requiring women on boards of publicly traded companies, he suggested it might not survive legal challenges.

Three years later, a judge will begin hearing evidence Wednesday in Los Angeles Superior Court that could undo the law credited with giving more women seats in boardrooms traditionally dominated by men. The California law has spurred other states to adopt or consider similar laws.

The conservative legal group Judicial Watch brought the lawsuit claiming it’s illegal to use taxpayer funds to enforce a law that violates the equal protection clause of the California Constitution by mandating a gender-based quota.

“They are creating a classification that either prefers or discriminates against one class or in preference of another,” attorney Robert Patrick Sticht said. He said the state doesn’t have a compelling government interest to create the mandate.

Another conservative legal group has filed a separate lawsuit in federal court claiming the law violates the equal protection clause of the U.S. Constitution.

Former Sen. Hannah-Beth Jackson, who authored the legislation, said the bill did not impose a quota because boards don’t need a certain percentage of women. Corporations can meet the requirement by adding women without undermining the rights of male board members.

She said the plaintiffs should be embarrassed for claiming the law is discriminatory.

“I find that to be incredibly ironic and hypocritical,” Jackson said. “Any time you try to make significant change to the status quo the powers that have been institutionalized to this kind of discrimination are likely to fight back.”

The law required publicly traded companies headquartered in California to have one member who identifies as a woman on their boards of directors by the end of 2019. By January, boards with five directors must have two women and boards with six or more members must have three women.

Penalties range from $100,000 fines for companies that fail to report board compositions to the California secretary of state’s office. Companies that do not include the required number of female board members can be fined $100,000 for first violations and $300,000 for subsequent violations.

Fewer than half the nearly 650 applicable corporations in the state reported last year that they had complied. More than half didn’t file the required disclosure statement, according to the most recent report.

No companies have been fined, though the secretary of state can do so, said spokeswoman Jenna Dresner.

The state has argued in court papers that it hasn’t used taxpayer funds to enforce the law. Dresner and the state attorney general’s office declined to comment on pending litigation.

Supporters of the law said it has already had a big impact in California and beyond. Washington state passed a similar measure this year and lawmakers in other states, including Massachusetts, New Jersey and Hawaii, have proposed similar bills. Illinois requires publicly traded companies to report the makeup of their boards.

Several European countries, including France, Germany, Norway and Spain, require corporate boards to include women.

Before the California law went into effect, women held 17% of the seats on company boards in the state, based on the Russell 3000 Index of the largest companies in the U.S., according to the advocacy group 50/50 Women on Boards. As of September, the percentage of board seats held by women climbed to more than 30% in California, compared to 26% nationally.

Still, some 40% of the largest companies in California need to add women to their boards to comply with the law, the group said.

With a deadline approaching, “there’s a lot of scrambling going on,” said Betsy Berkhemer-Credaire, CEO of 50/50 Women on Boards. She’s also heard anecdotally that other companies are waiting to see how the court rules.

Berkhemer-Credaire said she is confident it will be upheld. If it is found unconstitutional, it could slow progress, but she thinks pressure from institutional and private investors will continue to lead to more women being named to corporate boards.

“The train has left the station,” Berkhemer-Credaire said.

Adding pressure on the issue, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission in August approved Nasdaq’s proposal that most of the nearly 3,000 companies listed on the exchange have at least one woman on their boards, along with one person from a racial minority or who identifies as gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender or queer.

There’s no penalty for companies that don’t meet the Nasdaq diversity criteria, but they must publicly explain why they could not comply.

The Nasdaq rule and a California law signed last year requiring publicly traded corporate boards have a member by January from an underrepresented community — including Black, Latino, Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American, or someone who self-identifies as gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender — are also facing lawsuits.

When the California law was proposed, an analysis by the state Assembly noted: “The use of a quota-like system, as proposed by this bill, to remedy past discrimination and differences in opportunity may be difficult to defend.” Brown signed it amid the budding #MeToo movement over sexual misconduct.

“I don’t minimize the potential flaws that indeed may prove fatal to its ultimate implementation,” the Democratic governor said in a letter. “Nevertheless, recent events … make it crystal clear that many are not getting the message.”

Judicial Watch sued in August 2019 and the Pacific Legal Foundation sued three months later on behalf of a shareholder who said the law would force him to discriminate on the basis of sex. The latter case was thrown out by a federal judge, but revived by a unanimous panel of the 9th U.S Circuit Court of Appeals.

Although the California Chamber of Commerce had opposed the law, it didn’t sign on to the litigation and no company has joined the legal effort being led in Los Angeles by three California residents. They sued under a provision that allows taxpayers to prevent unlawful government expenditures.

![]()