China launches 6-month crewed mission as it cements position as global space power

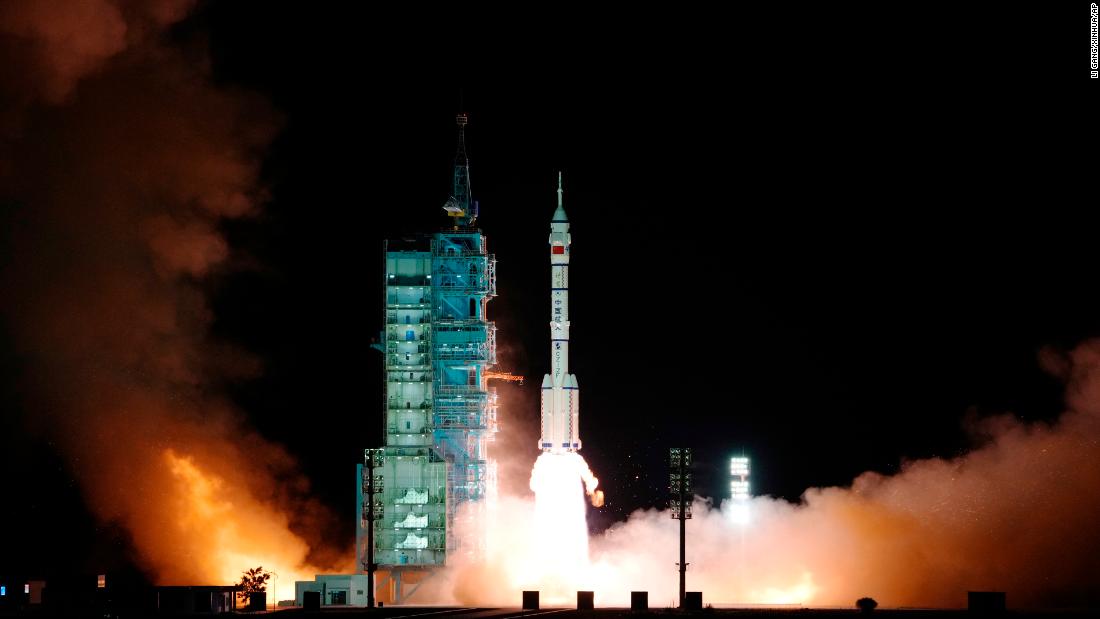

The three astronauts lifted off on the Shenzhou-13 spacecraft just past midnight local time, launched by a Long March 2F rocket from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in the Gobi Desert, located in Inner Mongolia.

They will dock at China’s new space station, Tiangong (which means Heavenly Palace), six and a half hours after launch. They will live and work at the station for 183 days, or just about six months — the country’s longest mission yet.

The crew includes Zhai Zhigang, Wang Yaping and Ye Guanfu, who will spend the time testing the station’s technology and conducting spacewalks.

Zhai, the mission commander, performed China’s first spacewalk in 2008 and has been awarded the honorary title of “Space Hero” by the government.

This will be Ye’s first mission in space; he is currently a second-level astronaut in the military’s Astronaut Brigade.

Six months is the standard mission duration for many countries — but it will be an important opportunity for Chinese astronauts to become accustomed to a long-term stay in space and help prepare future astronauts to do the same.

“In the first place, any crewed mission is significant, if only because space travel by humans remains a risky endeavor,” said Dean Cheng, senior research fellow at the Davis Institute for National Security and Foreign Policy. “This will certainly be their longest mission, which is quite impressive when you consider how early it is in their human spaceflight regimen.”

This is the second crewed mission during the construction of the space station, which China plans to have fully crewed and operational by December 2022. The first crewed mission, a three-month stay by three other astronauts, was completed last month.

Six more missions have been scheduled before the end of next year, including two crewed missions, two laboratory modules and two cargo missions.

“For the Chinese, this is still early in their human spaceflight effort as they’ve been doing this for less than 20 years … and for fewer than 10 missions,” Cheng added. “In the past, the Chinese put up a crewed flight only once every two to three years. Now, they’re sending them up every few months.”

“If the Chinese maintain this pace … it reflects a major shift in the mission tempo for their human spaceflight efforts.”

Lead-up to liftoff

CNN gained rare access to the launch this week, including a series of highly choreographed events and news conferences in the lead-up to Saturday.

The launch site looks as if it’s been dropped into the Gobi Desert in the middle of nowhere, hours away from the city, surrounded by barren brown plains of sand and rock. There is only one road cutting through the middle of the desert, then a swath of nothingness around it, only some low mountains in the distance.

The road near the site was littered with signs warning that it was a military area where no unauthorized entry was allowed. The country’s crewed space program is overseen by a military body, and many of the launch sites and satellites are run directly by the People’s Liberation Army.

Arriving at the launch center was like entering a miniature city, complete with sprawling roads, dormitories and stadiums. One billboard was plastered with the image of President Xi Jinping, next to the words “Chinese dream, space dream.”

China’s space program was late to the game, only established in the early 1970s, years after American astronaut Neil Armstrong had already landed on the moon. But the chaos of China’s Cultural Revolution stopped the nation’s space effort in its tracks — and progress was postponed until the early 1990s.

Space administrators picked two classes of astronauts in 1998 and 2010, laying the path for a rapid acceleration in space missions. Aided by the economic reforms of the 1980s, China’s space program quietly progressed until the launch of the first crewed mission in 2003.

“What is truly impressive about China’s space program is how rapidly it has advanced, on all major fronts, from a pretty low base as recently as the 1990s,” said David Burbach, associate professor of national security affairs at the US Naval War College.

“The European Space Agency, Russia, India, and Israel have suffered Moon or Mars probe failures in recent years; China succeeded with both on the first tries,” Burbach told CNN via email. Though the US still has the world’s leading space program, he said, “there’s no doubt that China is the world’s Number 2 space power today.”

China’s ambitions span years into the future, with grand plans for space exploration, research and commercialization. One of the biggest ventures will be building a joint China-Russia research station on the moon’s south pole by 2035 — a facility that will be open to international participation.

Politics in space

Even in space, there’s no escaping Earth’s politics.

Chinese astronauts have long been locked out of the International Space Station due to US political objections and legislative restrictions — which is why it has been a long-standing goal of China’s to build a station of its own.

As China’s space program expanded, some countries like Russia have reached out to collaborate — but others remain wary. It’s not clear, for instance, whether the European Union will cooperate with China in space — especially as skepticism in Europe about China grows after several recent diplomatic spats and controversies over politics and human rights, Cheng said.

The US, meanwhile, continues to stand separate. It’s not a complete ban on interaction, Cheng said — for instance, American and Chinese scientists can chat at international conferences — but the 2011 Wolf Amendment effectively shuts the door on true bilateral cooperation in space by prohibiting NASA from spending any money on interactions with China.

One reason space research cannot be divorced from terrestrial politics, and why the issue is so complicated, is because “the Chinese space program is heavily influenced, and its human and lunar programs are overseen, by the Chinese military,” Cheng said. “Cooperating with China in space means cooperating with the Chinese military.”

But Burbach, the professor, said the division between the countries “goes too far,” potentially blocking precious scientific progress.

“As things stand, US and Chinese scientists won’t even be able to trade samples of Moon rocks, which the US and Soviets did do during the Cold War,” Burbach wrote in an email.

Although he said the chill is “understandable” given the deteriorating US-China relationship, Burbach added that “many American allies are willing to engage with China on space exploration, and the US probably does not gain much from taking such a hard line.”

China might not need American assistance at this point. Already, China is significantly ahead of Europe, and catching up fast with the US, he said.

“The development of China’s manned spaceflight is based on our own plan. We have our strategy and our plan,” said Lin Xiqiang, Deputy Director General of the China Manned Space Agency. “We didn’t think about comparing with others.”

And though it has been excluded from the ISS, China’s space station might one day be the main one in operation, since NASA could retire the ISS by 2030.

If the US is “unable or unwilling to maintain a human presence in space,” China could gain an advantage and pull ahead, Cheng said.

That leaves a gap for China to fill — and even if the ISS remains open, the Tiangong space station could become a major rival. China will likely allow foreign astronauts from different countries to stay on the station and conduct experiments — increasing their “international prestige and diplomacy, just like the US,” Burbach said.

![]()