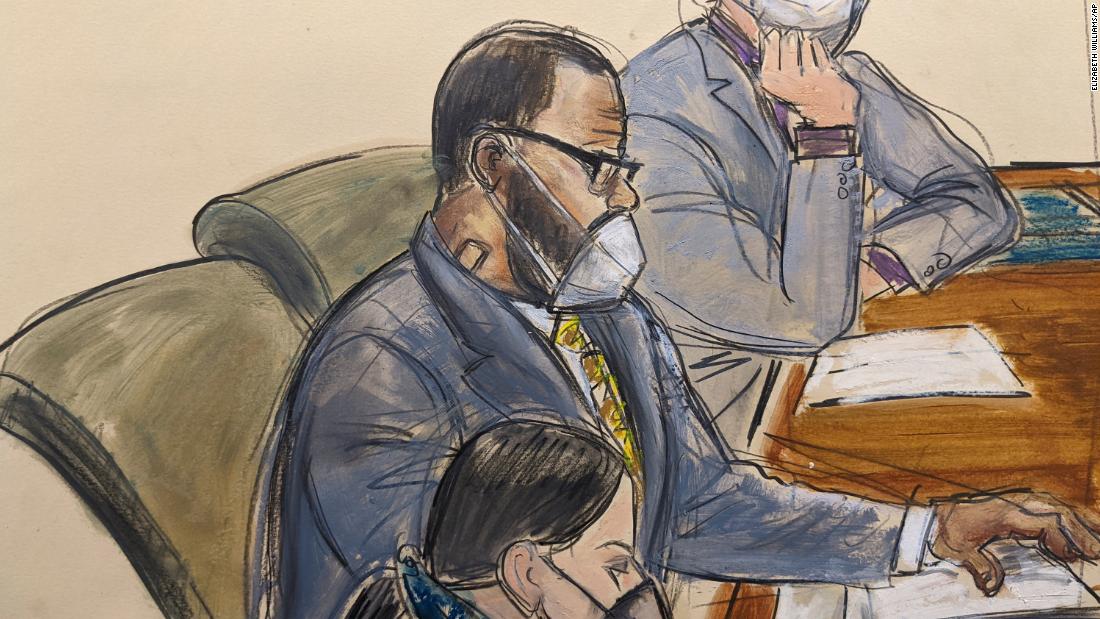

What we were not allowed to see at R. Kelly’s trial

US District Judge Ann Donnelly decided to keep media out of the courtroom less than a month before the August 18 start of the trial. Because of the pandemic, she said, jurors needed to be seated in the courtroom gallery because of social distancing recommendations and that it would be “inappropriate” to seat members of the press with them.

Donnelly’s decision created obstacles for journalists covering the trial. They couldn’t see important pieces of evidence or watch how the jurors reacted to testimony, among other issues.

And journalists could not voice their concerns in real time since they were placed in a courtroom two floors away from where Kelly’s trial was taking place.

Even during the trial of Mexican cartel leader Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, held at the same courthouse in 2019, the jurors and their reactions could be seen by the public, including the press. Guzman was ultimately convicted on all 10 federal criminal counts against him, including racketeering, and is spending the rest of his life in prison.

Roger Canaff, a former prosecutor who focused on cases involving sex abuse, said in his 25 years practicing he has never seen a jury completely blocked from the public’s view.

“The right to a speedy and public trial is fundamental in the US and the criminal justice process should not be shrouded,” Canaff told CNN. “Even in high-profile and emotionally charged cases, it is unusual for a judge to prevent the jury from being seen at all.”

The jury

Kelly, his legal team and prosecutors filed into Donnelly’s courtroom each day of the trial along with the jury. But journalists and the public who wanted to watch the proceedings were funneled into two different courtrooms on a different floor.

The proceedings were barely visible on two flat screens that featured security camera feeds showing a wide shot of the courtrooms. Witnesses’ faces appeared to be about the size of a quarter. It was difficult to tell whether witnesses became emotional on the stand. Evidence appeared in a black box on the screen that was too small to read.

The 12 jurors and six alternates briefly appeared at the bottom of the screens as they filed in and out of the courtroom. But they were cropped out of the view of the public, so their reactions to evidence or testimony couldn’t be seen. That’s something Bernarda Villalona, a criminal defense attorney who came to view Kelly’s trial as a spectator, said was a way to judge how jurors were feeling about the case.

“I’m looking at facial expressions. Especially when there’s vital witnesses, victims testifying,” Villalona told CNN. “That is very telling as to us as to where they stand with this case.”

Only for the jury

Journalists and the public could not raise their objections with the judge as prosecutors began showing key audio and video evidence to jurors wearing headphones.

The recordings, which Donnelly described in court as “somewhat upsetting,” were shown to jurors on September 15. The public could not see jurors’ reactions to them and did not know what they contained, aside from two recordings discussed in a September 14 filing from prosecutors.

According to the court filing, one video recording purportedly showed Kelly entering a room with two women in it and accusing one of the women of lying. Prosecutors say he “can then be heard beginning to physically assault the woman.”

In another recording, which prosecutors described as an hourlong audio file, Kelly confronted an unnamed woman for stealing a watch and “berated, threatened and physically assaulted her.” Prosecutors said he also told the woman people get “murdered” for doing what she did. These types of threats were central to the prosecutors’ case that Kelly used coercion to control his victims.

More than a dozen media organizations covering the trial banded together to ask Donnelly via letter for access to the recordings, which were not sealed. CNN was one of the news outlets that participated in the legal action.

“Because the materials were not sealed when they were presented to the jury, the Press Organizations now have an immediate right to access and to make copies of the video and audio evidence,” the letter states.

The letter said if the judge didn’t grant access to the recordings, then the media organizations wanted the opportunity to address the matter in court. The letter also asked the court to consider redacting any sensitive material to permit the public release of this evidence.

On September 21, Donnelly addressed the recordings in court, saying the media shouldn’t be allowed to see them, partly because of their graphic nature.

“It is extremely graphic. It would be embarrassing is an understatement. It would cause humiliation and create all kinds of other consequences (for the people in it),” Donnelly said in court.

Donnelly ruled that the media could listen to redacted versions of the audio from some of the recordings.

Shortly after this story published (and because of the media’s letter to the court), prosecutors allowed journalists to listen to audio-only versions of some of the evidence.

The files included recordings of Kelly threatening women and evidence of the women filming humiliating acts, but many were indiscernible because they did not contain dialogue. Donnelly also allowed several members of the media, including CNN, into the courtroom for the first time since the start of the trial to watch the jury deliver the guilty verdict.

For weeks, witnesses testified about a culture of threats and coercion while spending time with Kelly, and yet the public still hasn’t had an opportunity to see evidence of these threats, something Villalona said was an important part of the justice system.

“When you’re talking about the criminal justice system, members of the public have to be a part of the trial — they have to be able to see it. Transparency has to exist in order for there to be any trust in the criminal justice system,” Villalona said.

It wasn’t until the government delivered its closing arguments last week that the public finally learned more about the content of the recordings. In one, assistant US Attorney Elizabeth Geddes said, a woman was instructed to take off her clothes by Kelly, who told her, “Four licks (spankings),” confirming the woman’s testimony in court.

“On the video you saw the defendant spank (her) four times, and you saw the absolute anguish on (her) face as he spanked her,” Geddes said.

Another video clip, Geddes said, showed a woman being directed by Kelly to be “sexual and seductive with bodily fluids, feces, urine.”

During her closing argument, Geddes told the jurors that she would not play the clip again because they might “never fully erase that searing image” from their memories.

Correction: An image caption on a previous version of this story used the incorrect title for Nadia Shihata. She is an assistant US attorney.

![]()