Critics take aim at charitable money sitting in donor funds

Wealthy philanthropists have long enjoyed an advantageous way to give to charity: Using something called a donor-advised fund, they’ve been able to enjoy tax deductions and investment gains on their donations long before they give the money away.

These so-called DAFs set no deadlines for when the donations must reach charities; the donors themselves decide when and where the money goes.

Critics complain that because DAFs provide no financial incentive to quickly donate the money, much of it ends up sitting indefinitely in the accounts rather than being distributed to needy charities.

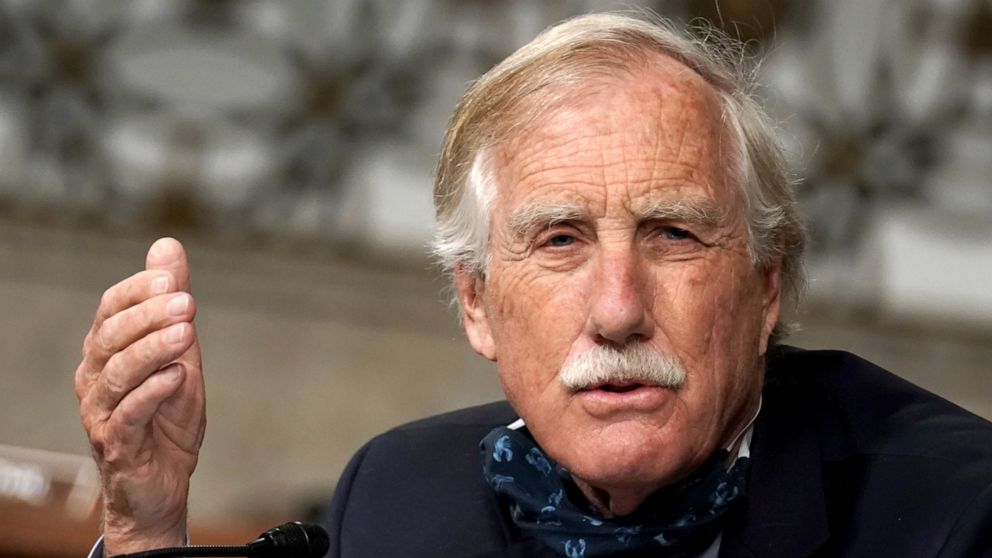

That criticism has helped drive a Senate bill that would tighten the rules for DAFs and aim to speed donations to charities. The bill, introduced by Sens. Angus King, a Maine Independent, and Chuck Grassley, an Iowa Republican, appears to be gaining bipartisan support in Congress.

The bill would make numerous reforms to DAFs by, among other things, creating new categories of accounts.

One type of account would give donors an immediate income tax deduction for money they agree to give to a charity within 15 years.

The second type would let them delay the distribution of their money for 50 years. These donors would get no income tax deduction until then. But they would still get to enjoy capital gains and estate tax savings for donating stocks or gifts into a DAF.

Community foundation-sponsored DAFs with less than $1 million would be exempt from the requirement. But donors with more than $1 million in such accounts would qualify for upfront tax benefits only if they distributed at least 5% of their assets annually or gave their money to a charity within 15 years. Under current law, assets can remain in a DAF indefinitely, tax-free.

“This is about as common sense a bill as I’ve ever seen,” said King, who caucuses with Democrats.

“The idea of getting a tax deduction today for money that may not be paid out for 50 years makes no sense,” the senator added. “I understand you might want to put it into a fund and have someone else manage it. But it’s got to go out within a reasonable period of time. Otherwise, it’s an abuse of the tax code.”

The proposed reforms have opened a rift in philanthropy circles among billionaire donors, community foundations and trade associations and have sparked intense lobbying efforts both for and against the legislation.

The debate was ignited when John Arnold, a Texas-based billionaire who made his fortune in hedge funds and now co-chairs Arnold Ventures, joined with a group of scholars and philanthropies to propose a set of reforms under a coalition they called The Initiative to Accelerate Charitable Giving. The group met with lawmakers to advocate for the reforms, which have largely been incorporated into the Senate bill.

What sparked Arnold’s interest, he said, was seeing rich people with philanthropic intent funneling money into DAFs yet distributing very little of it to charities.

“The money was just sitting there growing,” Arnold said. “There wasn’t any intent of abuse of the system. But the money was just building up because there was no forcing mechanism.”

Opponents of the bill counter that tighter restrictions on DAFs are unnecessary because the average annual payout rates for DAFs hover around 20% — much higher than the 5% minimum required of private foundations. Richard Graber, who leads the conservative Bradley Foundation, calls the legislation “a solution in search of a problem.” (The foundation is affiliated with Bradley Impact Fund, a DAF sponsor).

Yet without payout requirements, supporters of the legislation say DAFs — which hold an estimated $142 billion in the United States — have essentially become warehouses for charitable donations. The accounts let donors set up endowed accounts that exist in perpetuity and can pass on to their heirs.

A June report by the Council of Michigan Foundations showed that 35% of DAFs sponsored by Michigan community foundations distributed no money in 2020, a year marked by enormous need because of the viral pandemic.

Today, roughly 1 in 8 charitable dollars are estimated to go into DAFs. The New York Community Trust, a community foundation, established the first DAF in 1931. Their use accelerated in the 1990s, when Fidelity Charitable launched a national donor-advised fund program. Charitable arms of many financial firms, including Vanguard Charitable and Schwab Charitable, now run robust DAF programs.

Community foundations, along with universities, hospitals, faith-based groups and large charities like United Way also sponsor DAFs. Collectively, they account for a 300% growth in DAF accounts over the past 10 years, according to the National Philanthropic Trust.

Eileen Heisman, who leads the philanthropic trust, notes the ease of opening a DAF account online, the emergence of workplace charitable-giving accounts and low initial minimum contributions. Indeed, Fidelity and Schwab require no initial contributions at all for opening a DAF account, Heisman noted, thereby transforming it into a financial vehicle anyone can use. Still, the average value of a DAF account — estimated at about $162,000 — shows that DAFs remain a vehicle mainly for the affluent.

The Senate bill was crafted with guidance from Ray Madoff, a Boston College law professor who, alongside Arnold, has called for stricter DAF rules. Madoff and a colleague published a study in May that showed that working charities had lost $300 billion in contributions over a five-year period as more people channeled donations through DAFs and private foundations rather than directly to charities.

The Philanthropy Roundtable, a conservative-leaning group that opposes payout requirements for DAFs, disputes those findings. Its president, Elise Westhoff, argues that “more mandates and regulations on giving will just make it harder for all Americans to support the causes they care about.”

Supporters of the bill, including William Schambra, a philanthropy expert at the conservative Hudson Institute, say much of the pushback reflects a financial incentive that DAF sponsors want to preserve: The fees they charge to manage the accounts.

Some community foundation leaders agree.

“Community foundations’ business models are based on asset management,” said Paul Major, the CEO of the Colorado-based Telluride Foundation. “They charge fees, and that’s how they fund their operations. If they have less money to manage, they bring in less fees.”

“But the objective of charitable giving is not to manage more money,” Major said. “The objective is to put the money to work.”

Other experts agree on the need to rein in DAFs but favor a different approach. Edward A. Zelinsky, a professor at Yeshiva University’s Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, argues that creating a minimum annual contribution requirement for all DAFs would more effectively accelerate donations to charities.

Some community foundations say they think the bill is unnecessary because their organizations already have policies that incentivize faster payouts. Jeff Hamond, who oversees a coalition of 130 community foundations, contends that the legislation would increase the financial burden on community foundations, requiring them to track each donation.

“For every kind of additional cost burden you put on a community foundation,” Hamond said, “you’re actually driving more people to Fidelity, Vanguard and Schwab.”

The Senate bill would also prohibit donors from claiming tax benefits for complex donations — like real estate — that exceed the value of the gift. It would also incentivize private foundations to increase their payouts to 7% and bar them from meeting their payout requirements by paying salaries or other expenses for relatives or by donating to DAFs.

The Senate bill has been referred to the Finance Committee, though a vote hasn’t been scheduled. A spokesman for King’s office said the senator expects a bipartisan House version of the bill to be introduced in the coming weeks.

“I haven’t met anybody yet that I’ve described it to,” King said, ” who does anything but say, ‘Why didn’t we do this a long time ago?’ ”

———

The Associated Press receives support from the Lilly Endowment for coverage of philanthropy and nonprofits. The AP is solely responsible for all content. For all of AP’s philanthropy coverage, visit https://apnews.com/hub/philanthropy.

![]()