Captain’s death at sea stranded ship

For six weeks, the Italian-flagged ship was stranded off the Indonesian capital, Jakarta, unable to find a port that would take a corpse during the pandemic despite repeated pleas for assistance.

Finally, this month, the captain’s body was returned to his native Italy, where his grieving family are seeking answers about his death and treatment at sea, in a case that has once again thrown a spotlight on the conditions of seafarers during the pandemic.

Recovering his body, however, may not provide the answers the family is hoping for.

There was no suitable place to keep a corpse on the Ital Libera, meaning Capurro’s body remained in a storage room for six weeks.

“Without going into details, we all know how we can find it,” said the family’s lawyer Raffaella Lorgna. “I don’t even know if we’ll be able to do the autopsy.”

Death at sea

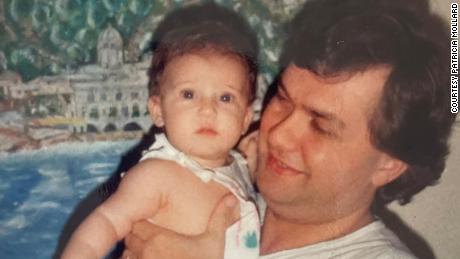

Capurro had worked on the ocean his entire life, both on cargo ships and cruise lines. His wife, Patricia Mollard, 61, followed him around the world wherever he went for his job. They met young and “lived for each other” Lorgna said. “I can only imagine the suffering of this lady,” she added. The couple lived in La Spezia, a port on the Italian Riviera, with their adult son and daughter nearby.

Capurro flew from Trieste, northeast Italy, on March 27 to captain the Ital Libera on its 25-day scheduled journey to Asia. A day earlier, he had tested negative for Covid-19. Flying through Doha and Johannesburg, he arrived in the South African port of Durban on March 28. A few days later, on April 1, the Ital Libera set sail for Singapore.

The captain started showing symptoms of Covid-19 on April 2. He was coughing non-stop and suffering from chest pains, muscle aches and shortness of breath, family members said. They quickly became worried. In emails, he became more erratic and incoherent by the day, according to his family; on the phone, his words were punctuated by a cough as he called from thousands of miles away.

By April 7, he was bed-bound in his cabin, according to his family. A sailor was assigned to bring him food and medicine. As captain of the ship, Capurro was also the designated medical officer so there was nobody else to help.

In the international shipping industry, many ships do not have dedicated medical officers on board. Instead, a seafarer with basic medical training is given the additional responsibility of administering health care. The medical responsibilities add to an already large workload for a shrinking global workforce, says Fabrizio Barcellona, the Seafarers’ Section coordinator for the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF), a global trade union.

Barcellona said anecdotally the number of ships operating with “manning levels” at or below what the federation regards as safe, was growing during the pandemic. Covid-era border restrictions brought in by national governments had made it very difficult for companies to get seafarers to and from ships, he said.

“The result is fewer crew to do the same amount of work. And the crew that are on board are tired, with many weeks or months over their initial contracts onboard.

“Seafarers are used to having to do lots of jobs on top of their day job. But during the pandemic the number of jobs is growing. For example, seafarers are being asked to perform remote inspections now because the flag states say they cannot safely board an independent inspector, and this is on top of seafarers’ six- or seven-day weeks.

“Unsafe manning levels are where you cannot perform all your expected duties — where you are torn between caring for a crewmate and watching the bridge and completing a remote inspection on the vessel’s safety. It’s too much and there will be poorer medical outcomes on board,” said Barcellona.

Capurro self-medicated with paracetamol and even found some oxygen aboard, his family said.

Mollard demanded medical care and — if necessary — to disembark the captain for treatment at the nearest hospital. Her request was refused, she said.

On April 11, Capurro took a rapid Covid test that came out negative, according to Mollard. Unconvinced by the result, she again called the ship’s operator — this time insisting her husband should be disembarked. But her plea went unanswered.

A day later, Capurro called his 38-year-old son, also named Angelo. Breathless and panting, he said: “I called you because your mother told me that you are very worried,” his son recalled. Angelo Capurro lied, not wanting to cause his father any more stress. “Don’t worry. I’m not worried, Dad. I trust you,” he said.

The next morning, Capurro died.

Infections aboard

The ship was three days away from Singapore. Mollard immediately contacted Italia Marittima, pleading with the operator to request the intervention of military ships in the area or to dock at a nearby port. “That’s the beginning of a grotesque and inhuman odyssey,” said Lorgna, the family’s lawyer.

A statement issued by Italia Marittima said the company, the Italian Ministry of Foreign affairs, and multiple Italian embassies appealed to a number of countries to disembark Capurro’s body, but Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, South Korea, the Philippines and South Africa had all implemented Covid restrictions that banned the disembarkation and repatriation of his remains.

With the ship anchored off Jakarta, two crew members — the first officer and a sailor who’d been in close contact with Capurro — were eventually permitted to disembark, according to Mollard.

It is unknown if the two seafarers were infected with Covid-19 and remains unclear how large the outbreak was aboard the Ital Libera.

“We regret to inform you that on the MV “ITAL LIBERA” Voy 066W, deployed in the SA1 service, some crewmembers tested positive for Covid-19,” the statement said. “As a safety measure, she has been anchored at the Port of Jakarta undergoing a 14-day quarantine.”

While the ship anchored, a new captain was brought aboard — this time following strict Covid protocols, according to Capurro’s son, Angelo Capurro.

The new captain had to stay in isolation for a week before being allowed to board the ship, Angelo Capurro said. He believes his father’s life could have been saved if he was disembarked and permitted to spend time in isolation after he started showing symptoms. “That would have been sufficient to save my father,” he said.

Lorgna, the family’s lawyer, filed a request with the La Spezia prosecutor’s office to investigate the captain’s death. According to the petition, “there is a need to carry out in-depth investigations aimed at clarifying the dynamics of the facts and any criminal liability.” The family is alleging charges against the company under “accident at work” and “failure to assist” clauses.

The prosecutor subsequently ordered the captain’s body to be returned to Italy as soon as possible for an autopsy.

In an email to CNN, an Italia Marittima representative said the company could not comment on the case due to the ongoing investigation and had also instructed its employees not to speak to the media.

Italia Marittima’s parent company, Evergreen Marine, has not responded to CNN requests for comment.

Pariah ships stranded at sea

Capurro’s story is far from unique during the pandemic.

Since March 2020, the bodies of at least 10 seafarers who died at sea have been held on ships, denied disembarkation to repatriate the remains, according to the ITF. None of those seafarers died from Covid-19, the ITF said.

As a result, crews are becoming more reluctant to leave their families and return to sea. “You’re going to get on a ship, we don’t know when you’re gonna come home. And if you don’t come home alone, we don’t know whether we’re going to get to say goodbye to your body,” McCourt, the ITF spokesperson, said.

Last year, as countries closed their borders to curb the spread of Covid-19, more than 200,000 seafarers became stranded at sea for months due to port closures, according to an ITF estimate.

In an ITF seafarers poll in March this year, 67% of the 593 respondents reported seeing signs of mental health issues, depression, and suicidal ideation among crew members. However, when asked if they themselves were experiencing mental health problems, just 52% of seafarers agreed. Barcellona said the results showed that seafarers could see the situation deteriorating for others on board, but were ignoring how the pandemic was affecting their own mental health.

“This is kind of the reality of what happens when everyone is focused on the big stuff around a pandemic,” McCourt said. “You can’t keep putting it all on these individuals, who are expected like a rubber band to keep being pulled and pulled and pulled. At some point, they’re going to snap.”

Family demands answers

Capurro’s family members say they still don’t know exactly how he met his death.

“We don’t know when he got Covid. We just know that when he departed from Italy he was healthy … but we don’t know if he was infected during the trip or on the vessel. We don’t know anything, not even if he died of Covid, we won’t know anything until the autopsy,” said Angelo Capurro.

“Not only I feel the loss of my father, I also feel that not all that was possible has been done for him.”

On May 26, six weeks after Capurro’s death, the Ital Libera finally set course for Italy to bring the body of its captain home.

“If they didn’t declare force majeure, the ship owner would have been out for a lot of money from the charter and the charter from the cargo owner,” said McCourt, from the ITF. “They will all sue each other down the line to the ship owner if they hadn’t declared force majeure, which is really sad because what it shows is that it has to be an act of God before we start recognizing the value and importance and pain of the humans at the heart of the system.”

On June 6, the captain’s daughter, Maria Capurro, 34, posted to Facebook a screenshot of the Ital Libera’s location off the coast of Yemen. “Dad, you’re on your way! I missed you a lot today. You would have loved today’s Formula 1 gp [Grand Prix]. I love you!!!!!!”” she wrote.

The Ital Libera arrived in the southern port of Taranto, Italy, on June 14 — almost two months to the day after Capurro’s death. His son and wife drove more than 900 kilometers (560 miles) from La Spezia to welcome home their loved one. “He would have done the same for me,” Mollard said.

To the blaring of the ship’s horn, Capurro’s body was lowered to land, one final salute to its captain. The local seafarer’s chaplain, Ezio Succa, said a prayer and gave a blessing.

“To see this ordeal, waiting two months for this moment, and finally to be able to be here on land, disembarked from the ship that was his life and has also become the place of his death,” he said.

“The life of seafarers is already very hard in normal times. With the Covid pandemic it’s worse.”

An earlier version of this article contained unapproved statements from the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF). It has been updated with comment from Fabrizio Barcellona, Seafarers’ Section coordinator for the ITF.

Additional reporting by CNN’s Hanna Ziady.

![]()