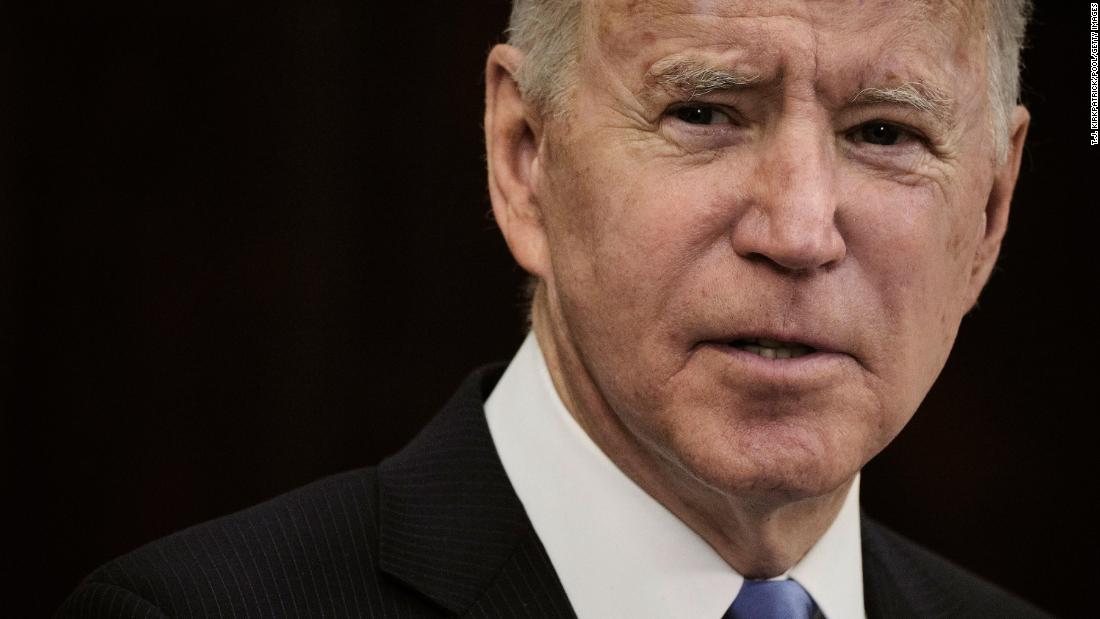

The President faces a moment of truth with a nation-changing agenda imperiled by a divided DC and resistance by pro-Trump Republicans

But the reality of a 50-50 Senate means he cannot even guarantee all of his own party is on side with his biggest goals.

Perceptions of the economy — always an important driver of political sentiment and key to a President’s authority — are caught in a strange limbo. Some signals are pointing to a bounce back to match the Roaring Twenties 100 years ago but other data on jobs and inflation offers an opening for GOP claims that Biden’s big government policies are inviting trouble.

A critical moment

During his first 100 days in office and in a largely successful attempt to scale distribution of the Covid-19 vaccines he inherited from Trump, Biden was able to ride a tide of public support based on the fact that at last a president was taking the pandemic seriously. Now, however, as he sets about implementing a partisan agenda, his political task becomes far more complicated. It is the nature of a presidency born in crisis to experience successive tests of authority and political dexterity. And Biden is about to face another one.

The President has made the push to find common ground on infrastructure reform the acid test of his vow to bring the country together that anchored his 2020 campaign and is a centerpiece of his entire presidency.

“I’m proud today of the United States. I’m proud today of our political system, the United States Congress. I’m proud today that Democrats and Republicans have stood up together to say something,” the President said.

Biden, however, may be the only person in Washington with such faith in a system seared by the most bitter partisanship, assaults on democratic norms by Trump and a fundamental disconnect on the purpose of government. Some Democrats believe the President is wasting time in negotiating with Republicans they think will never offer a counter proposal that comes anywhere near progressive hopes.

Still, Biden’s faith — or a desire at least to show voters he hasn’t given up on the aspirations that bankrolled his appeal to more moderate voters — led him to take a key role in talks with a small group of Republican senators that started with encouraging noises but seem to be foundering on the unbridgeable divide between the parties. If the President’s attempt to carve out a bipartisan infrastructure deal fails, it is hard to see any other issue where his vision of unity has any chance of being realized.

Republicans are balking both at Biden’s wide vision of infrastructure, which includes significant social spending and partially rolling back Trump’s corporate tax cuts to pay for it.

But the White House insists that its trimming of the package from $2.2 trillion to $1.7 trillion is a good faith offer to keep the GOP on board. There is a palpable sense in Washington that the crunch moment for the plan is approaching.

The problem for Biden is that a move to go it alone — to try to pass a bill based on Democratic votes with intricate parliamentary maneuvers in the Senate — could puncture the aura of unity and centrism with which he has cloaked his presidency and was important to the passage of his Covid-19 rescue bill.

Biden’s relationship with progressives is about to be tested in a big way

The President increasingly needs to be concerned about his left flank as well as the deteriorating hopes for talks on infrastructure with Republicans to his right.

Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, who chairs the Senate Budget Committee, sent a clear signal of progressives’ increasing impatience about bipartisan efforts that many of them feel do not enjoy good faith partners.

“We would like to have bipartisanship,” Sanders told CBS’s “Face the Nation.”

“But I don’t think we have a seriousness on the part of the Republican leadership to address the major crises facing this country, and if they’re not coming forward, we’ve got to go forward alone,” said Sanders, whose praise for Biden’s Covid-19 relief package provided cover for the President with liberals earlier this year.

But ties between progressives and Biden have been further strained by the behind-the-scenes role that the President took in mediating the fighting between Israel and Hamas last week as Palestinian casualties mounted.

Progressives are sensing that the President, despite embarking on a liberal economic agenda, isn’t firmly in their corner on everything.

“The progressives don’t like me because I’m not prepared to take on what I would say and they would say is a socialist agenda,” Biden said.

Such a worldview might help explain why Biden is keen to expand the social safety net with policies that help working Americans and tilt the balance of the economy back towards the less well-off but is reticent to embrace the expansion of the Supreme Court or ending the Senate filibuster.

The coming weeks will begin to define exactly whether Biden’s judgment of the political moment offers a path for his preferred way forward or whether he will have little choice but to turn to a more partisan approach to maximize what may be a narrow window to get big things done as the midterm elections loom.

![]()