Chicken, lumber, microchips, steel, gas and ketchup packets: What do they all have in common? They’re all (nearly) impossible to find.

Shortages are popping up across the supply chain as the pandemic messes with shipping, demand, supply and all the other levers of the global economy.

Here’s what’s hard to get, why and for how long, according to CNN Business’ writers.

Some restaurants removed chicken tenders and Nashville Hot flavored chicken items from menus at some restaurants because of limited supply, WSJ reported.

Chlorine

“The extent of the chlorine shortage is still unknown,” said B&B Pool and Spa Center, a Chestnut Ridge, New York-based retailer, on its website.

What’s clear is that pool owners should consider stocking up sooner rather than later. “With regard to retail pricing, it is a fact that we are seeing increases across the industry,” said Michael Egeck, CEO of pool supplies company Leslie’s, during a February earnings conference call.

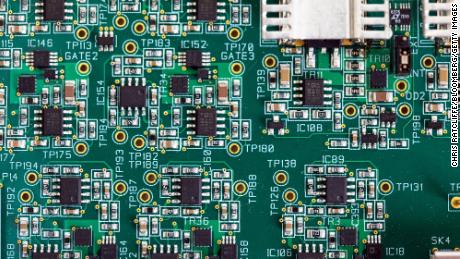

Computer chips

A growing number of manufacturers around the world are having trouble securing supplies of semiconductors, delaying the production and delivery of goods and threatening to push up the prices paid by consumers.

Several factors are driving the crunch, which was initially concentrated in the auto industry. The first is the pandemic, which plunged the global economy into recession last year, upending supply chains and changing consumer shopping patterns. Car makers cut back orders for chips while tech companies, whose products were boosted by lockdown living, snapped up as many as they could.

The shortage is going from bad to worse, spreading from cars to consumer electronics. With the bulk of chip production concentrated in a handful of suppliers, analysts warn that the crunch is likely to last through 2021.

Gas

It’s not that there’s a looming shortage of crude oil or gasoline. Rather, it’s the tanker truck drivers needed to deliver the gas to stations who are in short supply.

Between 20% to 25% of tank trucks in the fleet are parked heading into this summer due to a paucity of qualified drivers, according to the National Tank Truck Carriers, the industry’s trade group.

“We’ve been dealing with a driver shortage for a while, but the pandemic took that issue and metastasized it,” said Ryan Streblow, the executive vice president of the NTTC. “It certainly has grown exponentially.”

Gas prices, which typically rise at the start of the summer as seasonal regulations take effect — requiring the more expensive “summer blend” of gasoline needed to combat smog — are also rising.

The national average price of regular gas already stands at an average of $2.94 a gallon, up more than 60% from a year ago when prices and demand were bottoming out. The national average could surpass $3 a gallon this summer, and even get higher if any hurricanes hit the Gulf Coast or if there are any other disruptions to supply, such as a refinery fire.

Ketchup

How did this happen? It started with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention discouraging traditional, dine-in service at restaurants and suggesting more pandemic-friendly options like delivery and takeout instead.

Suddenly, restaurants coast to coast were packing up entrees, side dishes and cold beverages for a steady string of people working from home swirling past in their cars. Those customers expected condiments. So those traditional restaurants jumped into direct competition with fast food places, which had also shut down their dining rooms and upped their orders for ketchup packets.

Lumber

The shortage is delaying construction of badly needed new homes, complicating renovations of existing ones and causing sticker shock for buyers in what was already a scorching market.

Random-length lumber futures hit a record high of $1,615 on Tuesday, a staggering sevenfold gain from the low in early April 2020. That’s a big deal because lumber is the most substantial product that home builders buy.

The good news is that industry executives expect lumber production to catch up with demand — eventually. Samuel Burman, an assistant commodities economist, predicted in a recent note to clients that there will be a “sharp fall” in lumber prices over the next 18 months.

Metals

But they are all vulnerable to price volatility and shortages, the International Energy Agency warned in a report published this week, because their supply chains are opaque, the quality of available deposits is declining and mining companies face stricter environmental and social standards.

Limited access to known mineral deposits is another risk factor. Three countries together control more than 75% of the global output of lithium, cobalt and rare earth elements.

The Democratic Republic of Congo was responsible for 70% of cobalt production in 2019, and China produced 60% of rare earth elements while refining 50% to 70% of lithium and cobalt, and nearly 90% of rare earth elements. Australia is the other power player.

In the past, mining companies have responded to higher demand by increasing their investment in new projects. But it takes on average 16 years from the discovery of a deposit for a mine to start production, according to the IEA. Current supply and investment plans are geared to “gradual, insufficient action on climate change,” it warned.

Steel

Much like lumber, the steel industry was caught off guard by the rapid recovery in demand that began last summer — especially in the auto industry. “All of a sudden people were buying lots of cars,” said Tanners, the Bank of America analyst.

And it took time for America’s aging steel mills to resume the production they had sharply cut at the onset of the pandemic. Steel inventories shrank rapidly and shipments were delayed, just as steel buyers began ordering more than usual.

The good news, for steel buyers at least, is that analysts say all of the US steel production capacity that was idled during the pandemic has returned.

— CNN Business’ Chris Isidore, Paul R. La Monica, Matt Egan, Tom Foreman, Charles Riley and Hanna Zlady contributed to this report.

![]()