Experts say there’s an uphill battle brewing to get Covid-19 shots into arms

Nearly three months later, with plenty of vaccine supply on hand and eligibility open to all residents 16 and older, officials struggled to fill appointments, said Kristy Fryman, the emergency response coordinator and public information officer for the Mercer County Health District. About 264 people received their first dose at the district’s clinic earlier this month — roughly half the number of people who were signing up at the start of the rollout.

“People in rural areas tend to have an attitude of being self-sufficient, especially among the younger population,” Fryman said. “We’ve also heard people are waiting to get the vaccine because they’re wanting to know the side effects down the road from it. And then another comment would be that the vaccine is just too new.”

“We’re reaching the point where we’re getting to the hard audiences,” said Lori Tremmel Freeman, CEO of the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO). “The ones that either are unsure or on the fence about the vaccine, don’t have enough information or are just plain outright… not interested in the vaccine for other reasons.”

Experts, including Dr. Anthony Fauci, estimate somewhere between 70-85% of the country needs to be immune to the virus — either through inoculation or previous infection — to suppress its spread. But the US is nowhere near those levels yet and the slowing demand — especially now that eligibility has opened up — means getting there might be a taller task than some local officials expected.

A problem of demand

She told the United States Congress Joint Economic Committee on Wednesday that a major challenge for Covid-19 vaccinations in the coming months will be the demand: getting enough people signed up to take the shot. And there are several reasons why.

“The work that we’re doing on the equity piece needs to be done more deeply and done in the communities where people are living and working,” said NACCHO’s Freeman. “We have to be very creative in finding unique ways to reach people, including making sure that they have the easiest access possible to vaccine.”

In Mercer County, Fryman said officials are making efforts to make the vaccines more accessible, including events targeting the Hispanic population and initiatives to get more information to the Amish and Marshallese populations.

Other groups are hesitant, Gounder said, including younger Americans as well as what she calls the “moveable middle” — those who are on the fence but who may be swayed with more Covid-19 vaccine information.

“Then you have another group that is much more resistant, more entrenched in their views, it’s about 20% of Americans,” Gounder said. Those are more rural, conservative Americans who lack trust in the healthcare system and government, she said.

“That group is more challenging because it’s not necessarily a group that will respond to education the way that the sort of more moveable middle will,” Gounder said. “And that’s what we’re worried about.”

“It means that geographically you’re likely to have — not just according to rural versus not rural, but also referring to politics — certain populations that have lower vaccination coverage rates,” Gounder said. “And so… you’re likely to see more transmission within those subgroups.” And those populations, she added, could potentially seed spread back into other communities.

“I think it has a chilling effect,” Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, recently said on CNN. “I think people may wrongly think, ‘Well if it’s true with this J&J vaccine maybe it’s true with all vaccines.'”

Now, an ‘uphill battle’ for local officials

Officials in Lubbock, Texas, began noticing a slowing demand last month. The city, a small urban hub that’s home to Texas Tech University, is the county seat of a mostly rural county.

“We’re what people think Texas looks like,” said Katherine Wells, the city’s public health director. “Tumbleweed and dry.”

When Covid-19 vaccine appointments first opened up, demand was so high that callers crashed the city’s phone system, Wells said. By March, demand began dropping.

“We have a giant vaccination clinic that’s run out of (a) civic center, four days a week, we can do like 2,500 vaccines a day,” she said. “Starting about three weeks ago, we were unable to fill all those appointments.”

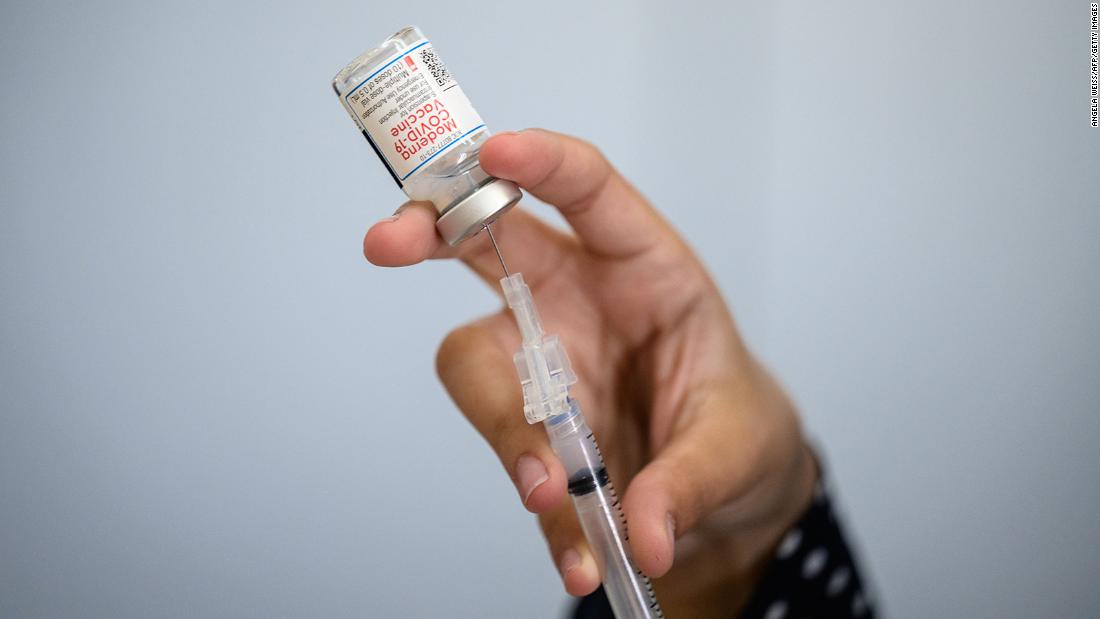

The J&J news, she said, “slowed us down even more.” The clinic, which can accommodate several hundred vaccinations per hour, averaged about 125 people hourly the day after the pause was announced, even though officials offered the Moderna shot to those who had J&J appointments, Wells said.

The demand shift underscores the challenge ahead for health officials, experts say.

“That initial demand with those high-priority groups and not to be able to sustain that with the general population means that we have really a lot of work to do, and we have to do it now, earlier than we perhaps thought we would have to do it,” Freeman said.

“I think we got the easy part done and I think it’s really going to take being in the community or finding people that need to be vaccinated and offering the vaccine with as few hoops as possible,” Wells said.

Local officials created a program targeting minorities and populations “that are usually turned away from healthcare,” Wells said, and have also begun pop-up clinics for all the major events in the area, including university sporting events, parades and other celebrations.

“I’d definitely like to get that higher,” David Gonzales said. “But again, there’s only so much we can do. We can promote it, we can ask folks, offer it, it’s free. We try to offer plenty of folks to get into a clinic. We try to make it as easy as possible, but there’s really only so much we can do.”

![]()