Hundreds risked everything in Selma 56 years ago today. This group is trying to identify them

She remembers the screaming and smell of tear gas as people ran back to the church seeking safety from the police. Many in the housing project — including her grandmother, no stranger to caring for freedom fighters — opened their doors to provide refuge.

Barnes Wilson didn’t realize it at the time, but she recalls seeing a bloodied Lewis, who had suffered a fractured skull and other injuries, loaded into a vehicle outside the church.

“At the time, I didn’t know what I was witnessing, but when I see old footage I have a flashback,” she told CNN. “I remember watching them bring that man out and put him in a station wagon because there was only one Black ambulance and … they were piling folks on top of each other to get to the hospital.”

“I read an article stating that you and a colleague were trying to locate participants of Bloody Sunday,” she wrote in her email. “My maternal grandmothers and I participated in the March. … I will never forget the sights and sounds of the horrible day.”

A sacred place crumbles as decades pass

Despite these remembrances, there are gaps, namely when it comes to understanding where the melee unfolded and who exactly took part.

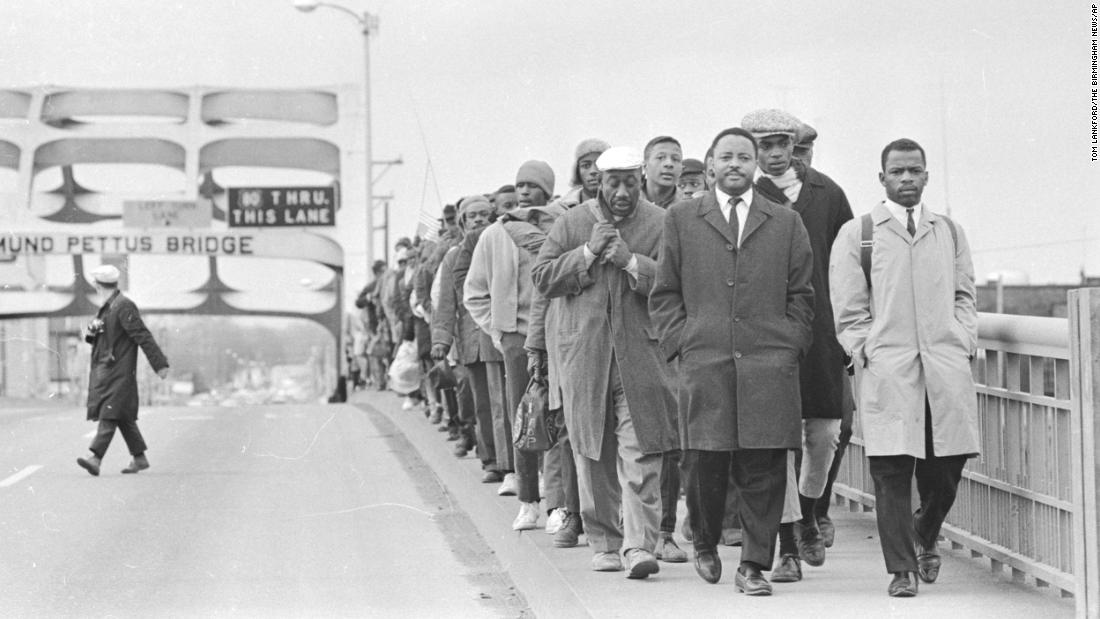

“Till they get to the Edmund Pettus Bridge, I don’t think (commuters) realize they just passed through where one of the most important moments in the civil rights movement took place,” Hébert said.

That began along a commercial stretch of highway about 300 yards south of the river, after protesters had marched through downtown Selma and crossed the bridge.

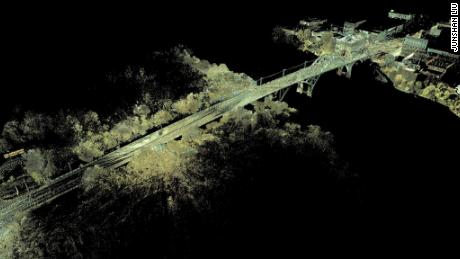

There’s a package store, a body shop and a curb market, but most of the stretch feels industrial and forgotten, as evidenced by the abandoned buildings with skeletal signs out front. What’s worse, Willkens and Lin noticed that each time they passed through en route to Auburn or Hale County, “things were noticeably deteriorating,” Willkens said.

There would be more broken windows in buildings. Facades were crumbling. Fasciae were falling apart.

“On the south side of the bridge, there is a mural to Bloody Sunday marchers, and we just kind of noticed that part of it was starting to come down,” she said. “Seeing this stuff right before your eyes put it in full focus.”

A scene is remade and lost voices summoned

“I was kind of shocked by what I saw as well,” he said. “It’s an internationally significant historic site, and it’s not being treated as such.”

The end goal was not only to memorialize the area but also to provide a teaching tool that would “allow you to step back in time and see what it was like,” Willkens said.

As part of that effort, Burt wanted, too, to commemorate the marchers. He, of course, knew Bloody Sunday presented a who’s who of the civil rights movement. In addition to Lewis, civil rights lions Amelia Boynton, Bob Mants, Albert Turner and Hosea Williams helped lead the march, but Burt wondered about the regular folks — seamstresses and brick factory workers who literally risked everything to take a stand that day.

He told one of his researchers, “Find me the list of all the marchers who were there on Bloody Sunday so I can start piecing this together.”

A search ensues for forgotten heroes

There was no list. There were the famous photos captured by James Barker, Spider Martin and Charles Moore, along with FBI photos. Reports from the bureau also included a list of people who were taken to the hospital.

If you were in Selma, Alabama, on March 7, 1965, and would like to tell your story or can help identify marchers, contact Auburn University’s Keith Hébert at heberks@auburn.edu or Richard Burt at rab0011@auburn.edu.

Yet for all their courage and all the stories told of their heroism, most of the 600 or so demonstrators who walked undaunted into that sea of vicious law enforcement on March 7, 1965, remain unnamed, unheralded.

“We are not aware of there being a definitive list of who marched on Bloody Sunday,” Burt said.

The group has teamed up with other educators, including a Selma high school teacher, and with Alabama State, a historically Black university in Montgomery.

In addition to scouring photos in hopes of determining who is this person walking by the Glass House restaurant or who is in this group being beaten in front of Haisten’s Mattress & Awning Co., the researchers also want to map their individual marches and retreats.

“Once we identify a name and the story behind them, we can track movements from Brown Chapel to the bridge to the other side to the state troopers and then the aftermath,” Hébert said. “Boil it down to the individual experience and commemorate the individuals … 600 men, women and children who participated in that march knowing full well the likelihood of what was about to happen.”

Hébert has added the effort to the curriculum. Some of his history students this fall will head to Selma for what he is calling “harvest days.” They’ll spend their time harvesting history in the hallowed hamlet of 18,000 people.

A daughter of Selma connects to her past

Once the pandemic passes, Burt hopes to get to the National Archives in Washington, DC, to collect more FBI photos and to the University of Texas’ Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, which houses work by photographers Martin and Moore.

“The end goal of it all is to provide a much richer story of what happened there that day,” Hébert said. “It’s much more than just the bridge, right?”

She worked as a poll worker last year in honor of her Aunt Shirley, who she said “stayed in jail” as a result of her activism. Barnes, despite her asthma, also fought hard for African Americans, she said.

Her grandmother, who passed in 2008, provided safe spaces for civil rights warriors traveling to Selma. Many were afraid to patronize local restaurants and hotels, but Barnes always had dinner for them and a place to rest their heads.

The 64-year-old recalls her grandmother once nursing three Canadian ministers, who were suffering from pneumonia and bronchitis, back to health, as they feared going to the local hospital because they were part of the movement.

Barnes Wilson and her grandmother left Selma for Boston in 1969, but she will never forget her days in south-central Alabama. Inspired by her aunt, grandmother and others in her family, she engaged in her own neighborhood activism as a young woman in Boston, she said.

Recently, she was going through a box of her grandmother’s things and found the young-adult book, “Martin Luther King: The Peaceful Warrior,” which brought back memories of her childhood, when she used to play with Sheyann Webb, who is now known as MLK’s “smallest freedom fighter” and coauthor of “Selma, Lord, Selma: Girlhood Memories of the Civil Rights Days.”

When Barnes Wilson read the online article about Auburn University’s work in Selma, she knew she had to do what she could to fill in any gaps and ensure the story was told — and told well.

“Because it made such an impact on our people. I look at the doors it opened for my grandchildren,” she said. “Selma made me the woman that I am.”

![]()