How White nationalists evade the law and continue profiting off hate

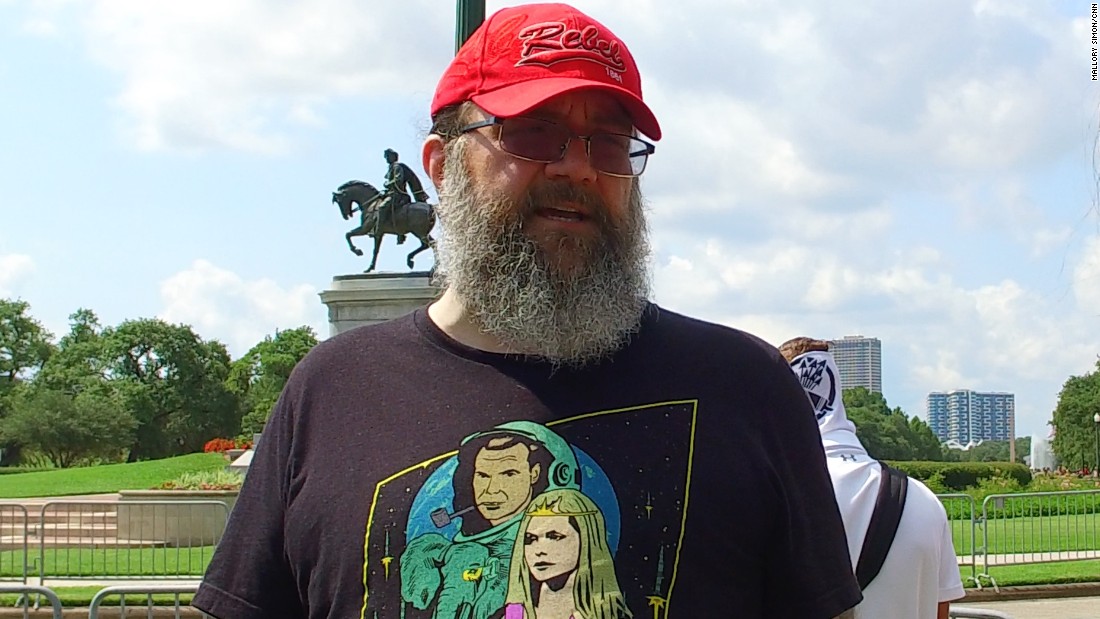

At the rally — which turned deadly — he participated with gusto, carrying a banner that, according to court documents, said, “Gas the kikes, race war now!” during a march past a synagogue.

But when Robert Warren Ray was indicted in June 2018 for using tear gas on counter-protesters at the event, police discovered he was nowhere to be found.

The fugitive, known in far-right circles as a prolific podcaster under a Bigfoot-themed avatar and the name “Azzmador,” has vanished — at least from real life.

However, Ray’s podcast, which he calls The Krypto Report, later appeared on a new gaming livestreaming service that has become a haven for right-wing extremists who have been deplatformed from YouTube and other mainstream social media channels.

Called DLive, the live-streaming platform with a blockchain-based reward system allows users to accept cryptocurrency donations — another perk for extremists barred from using services such as PayPal or GoFundMe, or who want to raise money internationally. Ray, a 54-year-old Texan, was a hit.

He quickly became one of the top 20 earners on DLive, according to an analysis by online extremism expert Megan Squire of Elon University in North Carolina, who studied the period from April 2020 — the earliest data available — through mid-January 2021.

It’s not just the police who are searching for Ray. Since September 2019, he has been flouting court orders and missing appearances in a civil case that names him as one of 24 defendants accused of conspiring to plan, promote and carry out the violent events of Charlottesville.

As for the criminal case, which charges Ray with maliciously releasing gas, authorities have labeled him a fugitive since his 2018 indictment.

To be sure, Ray — who mysteriously stopped podcasting from DLive a few months ago — didn’t get rich on DLive. But while he was ignoring court summonses for his alleged role in organizing Unite the Right, he earned $15,000 on the platform in just six months, according to Squire’s analysis. He cashed most of it out, she said.

“The idea that he’s wanted for all of this stuff, but then just gets to sit at home behind a microphone and make money on the side — I thought that was just not good at all,” Squire said.

Experts say the story of Ray and DLive underscores a reality about people who get chased into the shadows by lawsuits or deplatforming crusades: There will almost always be an entrepreneur who is willing to provide a venue for exiled promoters of hate.

“Where there is demand, eventually supply finds a way,” said John Bambenek, a cyber security expert who tracks the cryptocurrency accounts of extremists.

A game of cat and mouse

Public scrutiny drives alt-right personalities deeper into the bowels of the internet, reducing their visibility.

And while their retreat to ever more obscure corners can make it more difficult to monitor the chatter, Michael Edison Hayden, a spokesman for the Southern Poverty Law Center, says the game of whack a mole is ultimately worthwhile.

“I have seen firsthand the degree to which figures who were…extremely successful in radicalizing large numbers of people, become extraordinarily marginalized, extraordinarily fast in so-called dark corners of the internet,” he said.

This made it more difficult for laypeople to find his site, though it has managed to stay on the internet, partially through the work of an adroit webmaster. “There was just this ongoing battle of what (the webmaster) would do in order to keep Anglin’s voice online,” Hayden said.

The woman, Tanya Gersh, recently told CNN that she has yet to receive a dime of the judgment and is appalled that people are profiting from hate.

“If knowing that doesn’t disgust you, we have really, really been led astray in our country,” she said.

Although DLive initially allowed far-right figures — including Ray — it has purged several amid scrutiny in the wake of the deadly riot at the Capitol on January 6.

That day, Anthime “Tim” Gionet, better known as “Baked Alaska,” used the service to live-stream his role in the incursion. In the video, he curses out a law-enforcement officer, sits on a couch and puts his feet on a table, and can be heard saying, “1776, baby,” according to an FBI affidavit. Gionet was suspended from the site, as was Nick Fuentes — part of a White nationalist group of young radicals called the Groypers — who was also at the January 6 rally, though he says he did not enter the Capitol. Both had already been permanently jettisoned by YouTube and other social media outlets, though Fuentes remains on Twitter.

“DLive was appalled that a number of rioters in the U.S. Capitol attack abused the platform to live stream their actions,” and when its moderators become aware of the live streams, they shut them down, the company said in a statement to CNN. “All payments to those involved in the attack have been frozen.”

Ray’s DLive account, too, has been suspended, a company spokesman said, although the action did not publicly appear on his page until a couple of days after CNN reached out to the company on February 5. The DLive spokesman said the decision to sanction his channel was unrelated to CNN’s inquiry, and that the suspension amounts to a permanent ban.

In any case, Ray stopped posting to DLive about four months ago, around the time a judge in the Unite the Right case found him in contempt. He did not respond to CNN’s requests for comment.

Fuentes — DLive’s top earner, who took in about $114,000 in six months ending in January — has been scrambling to keep his podcast streaming since DLive booted him. For a few weeks, he’d figured out a way to keep using YouTube, even though the platform had dropped him, largely by using intermediaries to embed a livestream from other YouTube channels on his own website.

Squire said she spent those weeks engaged in a game of cat and mouse with him, repeatedly finding the 22-year-old Illinois native and notifying the third parties, and YouTube, of Fuentes’ actions.

The third parties have mostly acted swiftly and banned Fuentes’ content, Squire said. And while YouTube didn’t act on all of Squire’s initial reporting, the company took action when CNN flagged it.

“We’ve terminated multiple channels surfaced by CNN for attempting to circumvent our policies,” a YouTube spokesperson said last week. “Nicholas Fuentes’ channel was terminated in February 2020 after repeatedly violating our policies on hate speech and, as is the case with all terminated accounts, he is now prohibited from operating a channel on YouTube. We will continue to take the necessary steps to enforce our policies.”

Following YouTube’s crackdown, Fuentes began experimenting with other blockchain based technologies that enable him to stream his nightly program without being deplatformed. His recent moves have left Squire frustrated. “I don’t have an answer on how to do the take downs — I just don’t know,” she said.

Ray, meanwhile, appears to have retreated to another obscure streaming site, called Trovo, which is so new it is still in beta mode.

In the chat section of what appeared to be Ray’s new Azzmador page on Trovo, a follower said “we missed u Azz” on January 15.

Ray has yet to livestream any podcasts on Trovo. But in recent days — after several months of silence — a Telegram account bearing Azzmador’s logo with a link to his DLive channel burst back onto the platform with a series of racist and anti-Semitic messages.

“Harriet Tubman and MLK are both fake historical figures who had Communist Jew handlers/promoters,” read one February 7 message.

Some startups see the deplatforming of online firebrands as a recruitment opportunity.

“Hey @rooshv, so sorry to see you get censored!” a Canadian company called Entropy — which targets YouTubers and other streamers seeking to avoid censorship — tweeted at Daryush “Roosh” Valizadeh, an online personality in the so-called “manosphere,” who has touted misogynistic ideas such as that women are intellectually inferior and that rape should be legal on private property. Valizadeh — who authored an online post called “Why are Jews behind most modern evils?” — had just been dumped by YouTube less than a week prior, on July 13. “We would be honored to support your streams,” the tweet added.

In March 2019, Entropy’s three young founders were interviewed by a podcaster about their new product, and excitedly touted their first big-name user, Jean-François Gariépy, an alt-right YouTuber who frequently featured White nationalists on one of his shows.

“He was actually the first streamer to try us out,” said co-founder Rachel Constantinidis. “He tried us out for a number of months, and we were able to really improve the stability of the platform based on his feedback.”

Fuentes and Gionet did not respond to CNN’s requests for comment, and Valizadeh declined an interview.

How cryptocurrency comes into play

Just as far-right provocateurs are driven underground to more niche sites when they are booted from mainstream platforms, so, too, do they often gravitate towards cryptocurrency such as bitcoin when banished from using online payment services like PayPal and GoFundMe.

“Cryptocurrencies are indispensable to them at this point,” said Squire.

Because many of them were early adopters — and because bitcoin’s volatile value has recently skyrocketed — some are now sitting on vast sums.

Most successful in this realm has been Stefan Molyneux, a Canadian vlogger who has promoted ideas of non-White inferiority and has said, “I don’t view humanity as a single species.” Molyneux, dropped by PayPal in late 2019, starting taking bitcoin donations in 2013 and is holding onto a chunk of the cryptocurrency that amounted to more than $27 million as of Thursday morning, said Bambenek, the cyber security expert.

BitChute, Trovo and Entropy did not respond to CNN’s requests for comment.

Individual donations to far-right personalities mostly appear to have been small, and Bambenek said they are shrinking on the whole.

Anglin, who claims on his website to be banned from PayPal, credit card processors and even his PO Box, has been directing his donations to bitcoin since 2014. Over the years, he received more than 200 bitcoin, but most appear to have been cashed out, according to Bambenek, who said Anglin is holding on to at least 10.1 bitcoin, worth more than $525,000 as of Thursday morning.

But Anglin’s cryptocurrency holdings are becoming more difficult to monitor.

Azzmador and Anglin sued by Charlottesville victims

Demonetizing and deplatforming aren’t the only way to defang groups and individuals who espouse identity-based hate.

“You also need to sue them,” said Amy Spitalnick, executive director of Integrity First for America, a nonprofit civil rights group.

Ray and Anglin are among a couple dozen defendants named in a lawsuit underwritten by Spitalnick’s group on behalf of several activists who are Charlottesville victims. The two men are accused of being part of the leadership team that not only planned the Unite the Right rallies on August 11 and 12, 2017, but primed the pump for violence.

Four of the 10 plaintiffs in the civil rights lawsuit, which is scheduled to go to trial in October, were struck by the car driven by a neo-Nazi into a throng of counter-protesters, killing Heather Heyer, whose physical appearance Anglin would later disparage. Their injuries ranged from broken bones to concussions to torn ligaments. The other plaintiffs in the suit say they have suffered emotional distress either from physical injuries inflicted during the event or from psychological trauma and have missed work as a result.

In the days leading to the Unite the Right rally, much of the planning and coordination happened on The Daily Stormer, which — with Anglin and Ray as principal authors — began to take on a menacing tone, according to the suit.

On August 8, the suit says, Anglin and Ray said the purpose of the upcoming rally had shifted from being in support of a Confederate monument of Robert E. Lee, “which the Jew Mayor and his Negroid Deputy have marked for destruction” to “something much bigger…which will serve as a rallying point and battle cry for the rising Alt-Right movement.”

“There is a craving to return to an age of violence,” Anglin wrote, according to the suit. “We want a war.”

The Daily Stormer advertised the rally with a poster depicting a figure taking a sledgehammer to the Jewish Star of David.

“Join Azzmador and The Daily Stormer to end Jewish influence in America,” it said.

Prior to the event, the suit says, Ray and Anglin wrote on The Daily Stormer that “Stormers” were required to bring tiki torches and should also bring pepper spray, flag poles, flags and shields.

Anglin did not attend the rally in Charlottesville, but Ray did. During the march past the synagogue, the suit alleges, he yelled at a woman to “put on a fu**ing burka” and called her a “sharia whore.”

The suit says he then proclaimed: “Hitler did nothing wrong.”

Fast forward three-and-a-half years. By January, Ray’s once-prolific podcast had been dark for several months. His fans began to notice. On a forum called GamerUprising, somebody started a thread on January 25 called “What happened to Azzmador????”

“He just disappeared and no one even seems to care,” wrote the user, who goes by “Creepy-ass Cracker.”

But there are signs that Ray plans a return to podcasting as Azzmador.

On February 3, a fan on his Trovo page asked when Azzmador would begin streaming.

He responded in a word: “soon.”

CNN’s Julia Jones contributed to this story.

![]()