Analysis: A month into office, Biden seeks to reassure on the pandemic at home and abroad

Addressing back-to-back diplomatic meetings and making one of his first official trips outside of Washington as president on the same day, he communicated both the very real seriousness of the crisis and his willingness to fight it with investment in science and infrastructure both at home and abroad — a stark departure from his predecessor.

For four years under Donald Trump, the stature of the US was diminished around the world as many longtime allies watched the former President’s erratic behavior and anti-science pronouncements in disbelief. Though the US took the lead in past crises like the Ebola outbreak, which then-President Barack Obama referred to as a national security priority, Trump withdrew from that traditional posture as the coronavirus spread across the world, failing to marshal a coordinated national response even within the US as governors were forced to fend for themselves, despite his administration launching an effort to accelerate vaccine development and production.

“Even as we fight to get out of the teeth of this pandemic, the resurgence of Ebola in Africa is a stark reminder that we must simultaneously work to finally finance health security; strengthen global health systems; and create early warning systems to prevent, detect, and respond to future biological threats, because they will keep coming,” Biden told the Munich Security Conference, hours after he’d participated in his first virtual session of the G7.

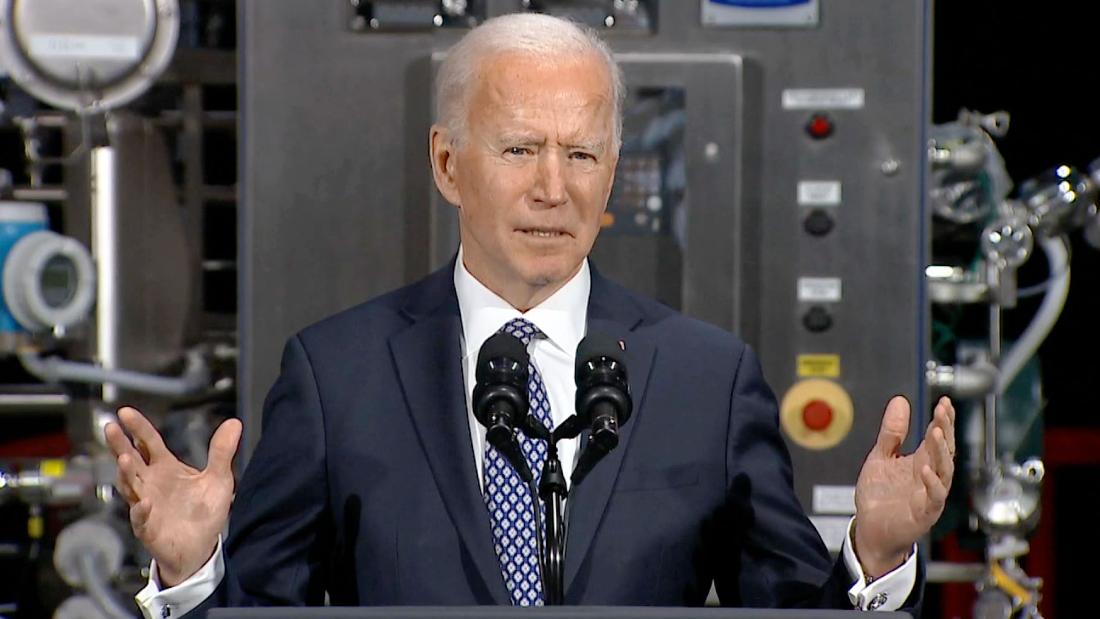

Later as he toured a Pfizer facility in Portage, Michigan — one of three sites in the US that is manufacturing the company’s vaccine — Biden tried to strike a balance between optimism and a realism about how quickly his administration could get the US population vaccinated and moving toward a higher degree of herd immunity. He pointed to the severe winter storm in Texas as an example of the unforeseen challenges that could slow the process, along with potential manufacturing delays and the new dangers posed by virus variants.

Harkening back to the promise that he made during his inaugural address, he noted that he told the American people he would always “give it to you straight from the shoulder, as Roosevelt said, because the American people can take the truth.”

“I know we’ll run into bumps. It’s not going to be easy here to the end, but we’re going to beat this. We’re going to beat this,” he said at the Pfizer plant where he inspected some of the ultra-cold freezers that hold the vaccine and toured another part of the facility where vaccines are boxed with dry ice.

He reiterated his belief that Americans should look toward the end of the year as a time when the US will be “approaching normalcy” but said he could not set a firm timeline for achieving that goal.

As of Friday, the US government had delivered more than 78 million doses of the vaccine to states and jurisdictions, according to the latest data published by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than 59 million doses have been administered, about 76% percent of what the government sent out.

During the White House coronavirus briefing earlier in the day on Friday, Slavitt said the federal government has a backlog of some 6 million doses due to weather and that all 50 states were affected.

Between the doses promised to the US by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna, along with the 100 million doses that Johnson & Johnson has said it would deliver of its single-dose vaccine by the end of July — if it is authorized for emergency use by the US Food and Drug Administration — the US could theoretically have enough vaccine doses to fully vaccinate the population by mid-summer.

“God willing this Christmas will be different than last — but I can’t make that commitment to you,” Biden said Friday. “There are other strains of the virus. We don’t know what could happen in terms of production rates. Things can change. But we’re doing everything the science has indicated we should do, and people are stepping up to get everything done that has to be done.”

Vaccine equity questions persist at home

“We got hit with three in 18 years that have been either pandemic or pandemic potential, so shame on us if we don’t develop the universal coronavirus vaccine,” said Fauci, the nation’s top infectious disease specialist.

Meanwhile, questions persist about how to get the vaccine distributed more equitably at home, particularly in communities of color where vaccine hesitancy is more pronounced, an issue the White House said it plans to bring into sharper focus over the next few weeks.

A Kaiser Family Foundation analysis showed that among those who have received at least one dose of the vaccine, White people have been vaccinated at a rate three times higher than Hispanic people and twice as high as Black people in the 27 states reporting ethnicity data.

One way the Biden administration said it is trying to address the issue is by opening new community vaccination centers in partnership with states. Two were opened in hard-hit areas of Los Angeles and Oakland this week, and Slavitt announced that five new sites would open in the next two weeks in Philadelphia, Orlando, Miami, Jacksonville and Tampa.

When questioned about the criteria used to determine the locations of those sites during the White House coronavirus briefing on Friday, Slavitt said the federal government works with states to find sites where they can target vaccinations to “those who are most vulnerable.”

While answering a question about vaccine equity, Slavitt also said that the administration will soon announce new steps to address some of the key barriers to vaccinations in some of the nation’s hardest hit communities. In those areas, many people have had difficulty getting the vaccine due to a lack of transportation and a lack of access to local pharmacies, providers and health clinics, not to mention the ability to get online and try to book scarce appointments that often are snapped up as soon as they are posted.

Slavitt said the administration is looking at solutions like bringing more mobile vans into those communities, adjusting the hours that vaccination sites are open to create more opportunity for shots outside the workday and helping fix some of the problems with the appointment systems.

“I can tell you that we are working (on) these in detail, along with the states, along with local communities,” Slavitt said. “I think it’s safe to say that if you don’t do the things — you naturally end up with the people who are getting hit hardest by the virus also getting the least access to the vaccine.”

“There are some success stories. I think it’s too early to report that we have figured this out,” he said.

“I think it’s a constant battle, to be honest.”

Ben Tinker and Maggie Fox contributed to this report.

![]()