The US economy added roughly half as many jobs last month as economists had expected

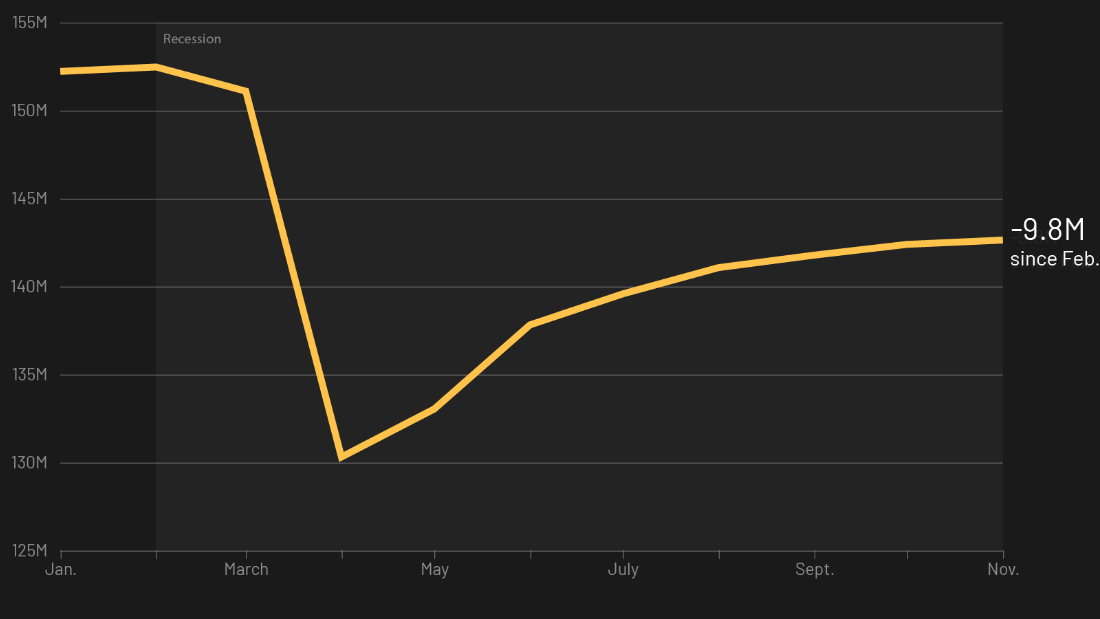

The economy is still down 9.8 million jobs since February, before the crisis began. That’s still more jobs than were lost during the Great Recession. If hiring were to continue at its current pace, it would take until March 2024 for the job market to return to its February 2020 peak.

The retail sector, which had been strengthening over the summer, registered a loss of 35,000 jobs because businesses hired fewer seasonal workers for the holidays.

Employment in government declined for the third month in a row, largely because of the loss of temporary workers hired for this year’s Census.

“The sharp slowdown in the pace of non-farm payroll gains to 245,000 in November underlines how the renewed surge in virus cases and restrictions is weighing on services demand, which will only intensify this month,” wrote Michael Pearce, US senior economist at Capital Economics, in a note to clients.

The real number of Americans out of work would total roughly 19 million, accounting for the number of officially unemployed, plus workers on temporary layoff, those who dropped out of the work force, and people who didn’t respond to the survey the jobs report is based on, according to Heidi Shierholz, director of policy at the Economic Policy Institute.

The jobs report is based on a survey conducted mid-month, and economists worry that it did not yet account for the full effect of the resurgence in infections.

The benefits cliff is coming

Many job seekers are worried about returning to an unsafe work environment and potentially exposing themselves or their loved ones to the virus. This is particularly true for those with preexisting medical conditions in their households.

Sean Blair, 35, from Ohio, who worked for a carpet cleaning businesses until he was furloughed due to the pandemic, is one of these people.

“I am unable to find a job and my extended unemployment benefits end on December 28,” Blair told CNN Business. “I have no idea what I will do to be able to pay my mortgage, utilities, car payment, and groceries once that income runs out.”

Jason D., 40, from New Jersey, who requested his last name be omitted for privacy reasons, bought a house with his wife and four children last year. After losing his job in March and helping his children with distance learning for the remainder of the pandemic, he and his family are worried what will happen when his benefits lapse.

His wife, Cindy, is now the breadwinner. “We’re keeping our heads above water because of unemployment [aid]. We will drown without it,” she told CNN Business.

The CARES act offered mortgage forbearance programs for struggling homeowners with government-backed loans, an offer followed by many other lenders. But many homeowners did not think they would need them, or worried about larger payments later, and didn’t apply.

For Margaret Hawkins, 64, also from New Jersey, the story is similar after losing her HR job in April. While the expanded unemployment benefits helped her pay her mortgage through part of the pandemic, she finally had to put her home on the market.

“It is a terrible way to end a career that I have loved, leave a town with wonderful friends and have to move to a part of the US with a cheaper cost of living,” she said.

Worse still, Hawkins also faced unemployment during the Great Recession just over a decade ago.

Some older workers say they had a hard time finding work even before Covid-19 hit. Now it’s even worse.

“I am being forced into retirement. I’m not ready to stop working. This surely was not my plan,” said Cynthia Rajski, 61, who worked for a printing business in Indiana until Covid-19 hit.

— Anna Bahney contributed to this story.

![]()