Mine developer sees review as positive for Alaska project

JUNEAU, Alaska — A proposed copper and gold mine that critics fear would imperil a major U.S. salmon fishery got a boost Friday with the release of an environmental review that the developer of the Pebble Mine sees as laying the groundwork for key federal approvals as early as this summer.

The environmental review released by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers suggested the Pebble Mine in southwest Alaska’s Bristol Bay region would not measurably affect fish numbers.

The Pebble Limited Partnership, which is owned by Canada-based Northern Dynasty Minerals Ltd. and is working to advance the mine, praised the corps’ work. Opponents called it inadequate and scientifically lacking.

The project has received what critics see as a lifeline during the Trump presidency, but there’s no guarantee it will be built. Besides permit approval from the corps and other federal agencies, the mine will need state approvals and, as currently proposed, access to lands that some landowners say they won’t provide.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which under the Obama administration proposed restricting development of the project, retains the option to invoke that so-called veto process again if it deems that warranted. Some argue a change in administration could affect the project’s trajectory. Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden was Barack Obama’s vice president.

Mine opponents also have vowed to keep fighting.

“I think as people dig into the document, they will find that the quality of the science is so lacking, there are so many gaps and so many flaws, that’s it’s going to be litigated from here to kingdom come,” said Tim Bristol, executive director of SalmonState, a group that advocates for salmon and salmon habitat.

Tom Collier, Pebble partnership CEO, saw the review as a cause to celebrate, calling it a significant milestone and validation for the project.

The Pebble partnership saw as unfair the attempt to restrict development, which was never finalized and dropped by EPA last year. The company argued the proposed restrictions were based on hypothetical mine plans and that the project should have a chance to go through the permitting process.

Dennis McLaren, who was an EPA regional administrator during the Obama administration, said EPA drew from Northern Dynasty documents in its analysis.

Collier has expressed confidence in the outcome of the current corps process, saying Pebble believes the planned mine “will be judged to be a project of merit” and receive a favorable permitting decision as early as this summer.

Northern Dynasty, for years, has been looking for a partner, and Pebble sees securing approval from the corps as aiding that effort.

The corps, when it makes a decision, could issue a permit, approve a permit with conditions or issue a denial. Joel Reynolds, a senior attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council, said a denial wouldn’t prevent Pebble from filing another application. But he said a denial would be the “final nail in the coffin for any further investor interest.”

The corps must wait at least 30 days from the publishing of the environmental review before entering a record of decision.

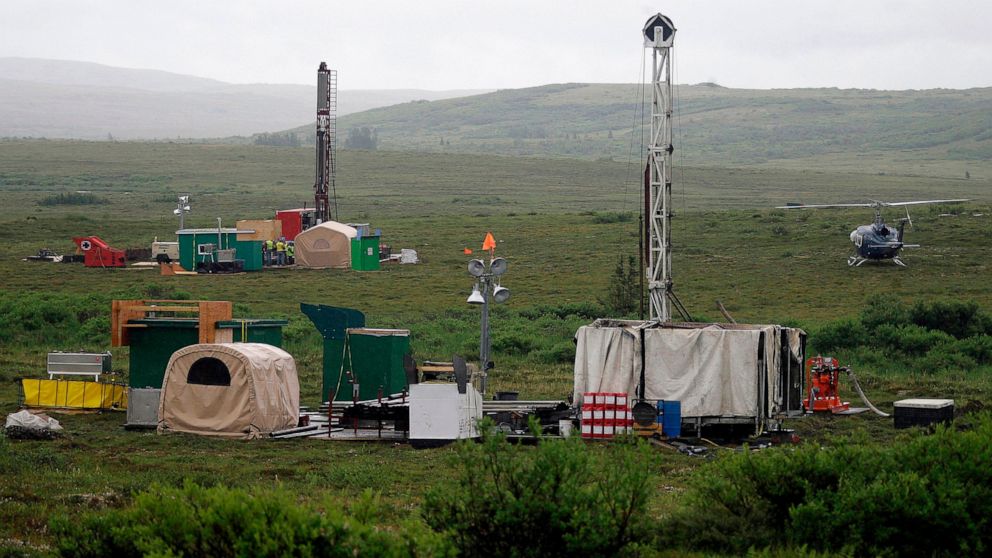

Pebble is proposing an open-pit mine and related infrastructure. The partnership, on its website, says the mine “will NOT harm the fish” and that the permitting process will validate that. It says the Pebble Mine would create jobs.

Collier said in the environmental review process, the corps was designated the umpire.

“We took our science to the corps and the other side took their science to the corps and the corps was the umpire and they called it our way,” he said.

The EPA has said the Bristol Bay watershed supports the largest sockeye salmon fishery in the world. Salmon also is important to Alaska Native communities that rely on it for subsistence.

The corps review states that under normal operations, the alternatives it looked at “would not be expected to have a measurable effect on fish numbers and result in long-term changes to the health of the commercial fisheries in Bristol Bay.”

Under the alternative, identified as Pebble’s preferred option, the direct impact area would include permanent impacts to about 2,230 acres of wetlands and other waters and 105 miles of streams, and there would be temporary or indirect impacts to others, according to the report.

The corps said it made changes based on comments to an earlier released draft and filled gaps identified in the draft, including for wetlands and vegetation data.

Frances Leach, executive director of United Fishermen of Alaska, in a statement said the review “is not the thorough, science-based assessment that we were promised.”

Pebble critics say the corps’ review has been rushed and questioned the feasibility of a proposed route that crosses land that Pebble does not have permission to use. The corps previously said it had preliminarily determined a northern transportation route to be part of a “least environmentally damaging practicable alternative.”

The Igiugig Village Council, in a statement, said its lands in the area are not available for use. The council “is committed to the sustainability and health of future generations and Pebble does not fit into our vision for a thriving future,” the statement said.

Mike Heatwole, a Pebble spokesperson, has said Pebble intends to engage with landowners along the northern route and believes it “will be successful in obtaining access to the transportation corridor necessary for the project.”

Collier said work remains on mitigation plans that will be factored in as part of a final decision.

![]()