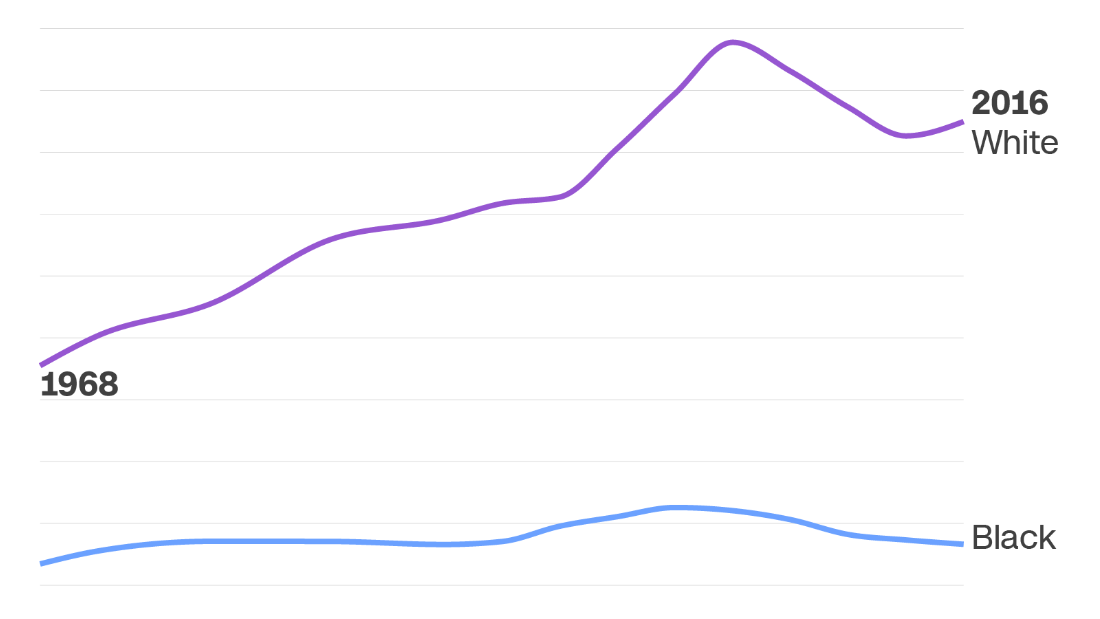

These charts show how economic progress has stalled for Black Americans since the Civil Rights era

“Over the last half century, I would say that for many indicators, things have stagnated,” said Ellora Derenoncourt, assistant professor of economics and public policy at University of California, Berkeley. “The wealth gap, the income gap, the earnings gap.”

The wealth chasm narrowed somewhat in the intervening years, until the financial crisis just over a decade ago. More Blacks became homeowners, but factors such as continued residential segregation meant that the value of their housing — and their net worth — did not grow as much as it did for White homeowners, said Edward Wolff, an economics professor at New York University. Also, Black families tended to have higher levels of mortgage debt.

The mortgage crisis that triggered that economic collapse reversed those gains. Home ownership rates among Blacks plummeted from nearly 50% in 2004 to the low 40%-range in recent years — a level not seen since the 1960s, according to the Urban Institute. Congress enacted the Fair Housing Act in 1968 with the goal of prohibiting racial discrimination.

“They were slammed a lot harder than White families by the house price collapse,” Wolff said of Black homeowners. “Lower incomes plus a credit crunch meant that they were left out of the housing market even after 2010.”

The median income of Black households grew from the late 1960s into the 1970s in the wake of several federal reforms, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited discrimination in employment and created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. This helped shrink the difference between the median incomes of Black and White families during that time, experts said.

Also, a broadening of federal minimum wage coverage to agriculture, restaurants, nursing homes and other services — where nearly a third of Black workers were employed — helped narrow the earnings gap between Black and White Americans during that period, said Derenoncourt, who researched the impact of the 1966 Fair Labor Standards Act.

After that, the divide widened again as Black Americans lost ground.

Researchers point to a variety of factors to explain the reversal, including a weakening in federal efforts to combat structural racism and a decline in unionization, as well as an increase in the number of families headed by single Black mothers and in the incarceration rates of Black men. And while Black Americans have acquired more education, they are still underrepresented in higher-skilled, better-paying jobs.

By 2019, the average earnings ratio between Black and White Americans had fallen back to where it was in the 1970s for both men and women, according to an analysis by Samuel Myers, Jr., director of the Roy Wilkins Center for Human Relations and Social Justice at the University of Minnesota.

“We have failed to change the mechanisms by which we reproduce wealth, by which we reproduce skills, by which we reproduce market outcomes,” Myers said. “And it’s race related.”

One area where the racial gap has shrunk over the last five decades is poverty.

In 1970, there were nearly four times as many non-Hispanic Black Americans in poverty as non-Hispanic White Americans. In 2018, that ratio was about 2.6.

A more consistent narrowing of the divide began in the 1990s, a period of economic prosperity and a hot labor market. Also, some government programs for low- and moderate-income Americans — such as the Earned Income Tax Credit — were adjusted to make work more attractive. And Congress overhauled welfare in 1996, reducing assistance to families and prioritizing employment.

The trend continued even during the 2008 crisis, which increased financial distress among all Americans, and in recent years.

Still, roughly one in five Black Americans are living in poverty, said Christopher Wimer, co-director of the Center on Poverty & Social Policy at Columbia University.

“While that has come down a lot in the past 50 years, it’s still a shockingly high number,” Wimer said.

Another area where the gap between the races is narrowing is the share of each group who is employed. That difference has been cut nearly in half since 1972, though all of the improvement has been in this decade, which saw steady job growth until the coronavirus pandemic struck in March.

“In tight labor markets, African Americans who have been previously excluded are now gaining employment,” said Olugbenga Ajilore, senior economist at the left-leaning Center for American Progress.

Until the outbreak, unemployment had been at or near 50-year lows for several months.

Still, problems that have plagued Black Americans for decades persist. Ongoing hiring discrimination has kept the Black jobless rate at or above twice the White unemployment rate for much of that time, Ajilore said.

“This positive era still had underlying issues, which this pandemic has made clear,” Ajilore said.

![]()