California tells hospitals to consider having a lottery for sought-after Covid-19 drug

But there’s not nearly enough to go around, and on Monday, one state health department directed hospitals to consider holding a lottery for scarce medications.

The federal government this week sent the California Department of Public Health enough medicine for 100 to 200 patients, depending on how long they take the drug. The state has more than 3,000 patients in the hospital with coronavirus.

On Tuesday, the state’s health department posted a distribution list. San Francisco, for example, was allotted enough doses for three to five patients, but the city currently has about 70 patients hospitalized with Covid-19.

Asked about the allocation of remdesivir, CDPH pointed CNN to guidance the department issued on Monday on how to allocate scarce medications for Covid-19.

That guidance suggests establishing a “prioritization” committee of doctors, nurses and others to help allocate the drug to patients.

It also suggests that “random allocation among patients be considered,” such as “using a lottery system to select a certain proportion of patients who become eligible for the drug.”

California isn’t the only state with tough decisions to make. Texas has some 1,600 patients in the hospital with the novel coronavirus but received only enough remdesivir for 100 to 200 patients.

That leaves doctors in a tough spot.

“You’re trying to get the most you can out of a limited resource,” said Alta Charo, a bioethicist at the University of Wisconsin. “There’s no perfect way of doing this.”

A ‘bungled’ distribution of a sought-after drug

It’s been a little over two weeks since top health expert Dr. Anthony Fauci first announced that a large study showed remdesivir worked against Covid-19, calling it the new “standard of care” for patients.

The drug doesn’t necessarily save lives, but it has been shown to shave four days off a hospital stay, Fauci said.

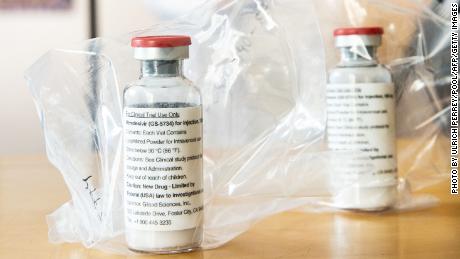

Gilead, the company that makes remdesivir, donated supplies of the drug, which exists only as an intravenous treatment, to the US Department of Health and Human Services for distribution.

Last week, HHS sent boxes of the drugs to some hospitals in seven states, without explaining how they chose those hospitals.

Then HHS sent the drug to health departments in six states, again not explaining how or why they selected those states. The agency just said the drugs would be used to treat patients “in areas of the country hardest hit by the pandemic.”

Rep. Lloyd Doggett, a Texas Democrat and chair of the House Ways and Means Health Subcommittee, called the distribution “bungled.”

Wednesday, he wrote a letter with Rep. Rosa DeLauro, a Connecticut Democrat who chairs the Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education Appropriations Subcommittee, and called upon HHS to explain its distribution formula.

On Monday, in a call with governors, HHS Secretary Alex Azar said remdesivir was being shipped to all 50 states “based on states’ needs” and that the shipments should arrive Tuesday.

He said his department would be shipping 75,000 doses, enough to treat approximately 9,700 patients, according to audio of the call obtained by CNN.

Azar was sympathetic that tough decisions needed to be made.

“We recognize that allocating treatments in a scarce environment is a complex, difficult decision,” he told the governors.

He also acknowledged issues with the distribution.

“The administration heard that on the first couple of distributions — supplies were not always getting to hospitals most in need,” he said.

At a Senate hearing Tuesday, Dr. Stephen Hahn, the commissioner of the US Food and Drug Administration, reflected on the distribution process.

“I think we can all agree upon the fact that we’ve learned a lot of lessons from the remdesivir situation,” he said, later adding, “I think valuable lessons can be learned and will be learned with respect to other therapies, and to vaccines in particular, and we must incorporate those into our operational plans moving forward.”

A lottery for a drug

Given the shortage of remdesivir, the idea of having a lottery is “the most fair and the least fair” method of rationing the drug, said Charo, the bioethicist.

On the one hand, it leaves the decision entirely to chance, and so no one can accuse the hospital of being biased for or against any particular patients.

On the other hand, it leaves no opportunity for doctors to make judgements about which patients would benefit the most by remdesivir.

“There’s no perfect system — just different concepts of fairness,” said Charo, a professor at the University of Wisconsin School of Law.

Massachusetts General Hospital, one of the earliest to receive shipments of remdesivir, has formed a committee to decide who will get the drugs. The committee includes pharmacists and physicians and ethicists who review patients’ medical records and then make allocation recommendations.

Intentionally, the committee does not include the doctors who are personally treating Covid-19 patients, according to Dr. Rochelle Walensky, chief of infectious diseases at Mass General.

Charo supported that decision.

She said if a patient’s doctor is a particularly effective advocate, it would put that patient at an unfair advantage and conversely, if a physician is an ineffective advocate, it would put the patient at a disadvantage.

Plus, individual physicians bond differently with different patients, and so might not fight for them equally.

“We can’t assume that physicians bond with all patients equally,” Charo said. “What if the doctor and the patient speak different languages? Or come from different backgrounds?”

She said a committee like the one at Mass General faces several difficult decisions. For example, do doctors give remdesivir to patients who are critically ill, since they’re in the most danger, or do they give it to patients who are not as sick because the drug might be more effective at an earlier stage of illness.

“What is your top priority? What is your top value?” Charo said.

Charo looks back at discussions she’s been involved with over the years about allocating limited resources, such as organs for transplantation. She imagines that those difficult discussions might be going on right now at hospitals across the country about how to ration remdesivir.

“I can still rehearse in my mind certain hospital ethics committee meetings that took place over 20 years ago. They were painful situations with people who all wanted to do the right thing and fundamentally disagreed with what the right thing was,” she said. “Reasonable people can disagree.”

![]()