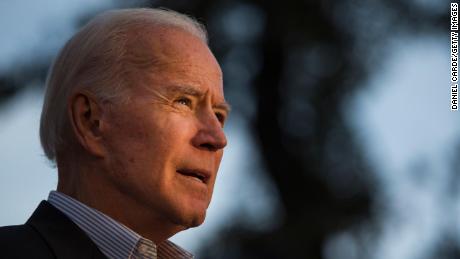

Massive pandemic casualties haven’t changed the President’s approval ratings much, but he still faces two big obstacles to reelection

The political landscape has turned upside down since 1992. When Republicans sought their fourth consecutive presidential victory that year, California and New Jersey were still reliably red states. The post-Civil Rights-era voter realignment remained incomplete.

Looser partisan attachments gave changing economic conditions more power to change a president’s political standing. The first President Bush saw his Gallup approval rating soar to 89% as America triumphed in the first Gulf War, then plunge below 40% when voters’ attention turned to the economic recession underway at the same time.

Americans rejected Bush’s leadership decisively, even when recession had turned to recovery. Elected in 1988 with 53% of the vote, Bush drew just 37% during his reelection in a three-way race that included an independent bid by Texas businessman Ross Perot.

“It didn’t matter what Bush said,” recalls Daron Shaw, who worked as a young data analyst on the Bush campaign and who now helps direct polling for Fox News. “As soon as you put Bush and economy in the same sentence, people just tuned out.”

That made Bush just the third president in the last century to lose reelection, all three with profound economic liabilities. The dispiriting stagflation of 1980 helped Ronald Reagan oust Democrat Jimmy Carter; the Great Depression fueled Franklin Roosevelt’s rout of Republican Herbert Hoover in 1932.

The starkly-divided political world Trump inhabits reduces the importance of economic issues. Strong growth for most of his term didn’t push Trump’s job approval even as high as 50%, or prevent his Democratic adversaries from recapturing the House in 2018.

Nor have the fearsome coronavirus casualties much changed the President’s chronically weak approval ratings. Polarization gives him a sturdy political floor. Voters may also be uncertain how much responsibility he bears for a disaster afflicting the entire world.

That’s how Trump parried Friday’s Depression-level unemployment numbers. He recalled the robust economy of just two months ago — and the deliberate choice to shut it down as coronavirus spread.

Typically, an incumbent president’s share of the vote closely resembles his job approval rating. Trump’s 45% approval last month in CNN’s Poll of Polls nearly matches the 46% of the popular vote he received in defeating Hillary Clinton four years ago.

But Trump faces two big obstacles to recreating his 2016 magic.

First, his share of the vote in polling matchups against Biden has run significantly behind his approval rating. That shows even some otherwise Trump-friendly voters weary of the incumbent’s divisiveness and erratic behavior.

In the national Fox poll last month, for example, 49% approved Trump’s job performance but just 41% planned to vote for him against Biden. Fox polls in the battlegrounds of Florida, Michigan and Pennsylvania pegged the gap at eight, six and five percentage points, respectively. Biden led in all three states.

“I haven’t seen a gap of that magnitude,” observes Shaw, who also teaches political science at the University of Texas.

Second, the health and economic toll of coronavirus complicates Trump’s ability to make up ground. Already, polls show Biden running especially well among senior citizens, the group most vulnerable to the coronavirus.

By shifting his message to economic re-opening, Trump aims to identify himself with the rebound the White House predicts will come later this year as Americans head to the polls — though health experts are already warning of a second wave of infections in the fall that might shut the economy down again.

If the US escapes that fate, though, it will fall to Biden to persuade Americans that Trump’s halting coronavirus response made their economic pain worse than it had to be. that argument could appeal to the modest pool of swing voters and prod others normally disaffected from politics to go the polls.

“Democrats have to make the case,” says Paul Begala, a principal architect of Bill Clinton’s 1992 economic offensive. “The narrative has to be, ‘He’s doing a horrible job for you. He’s hurting you.'”

![]()