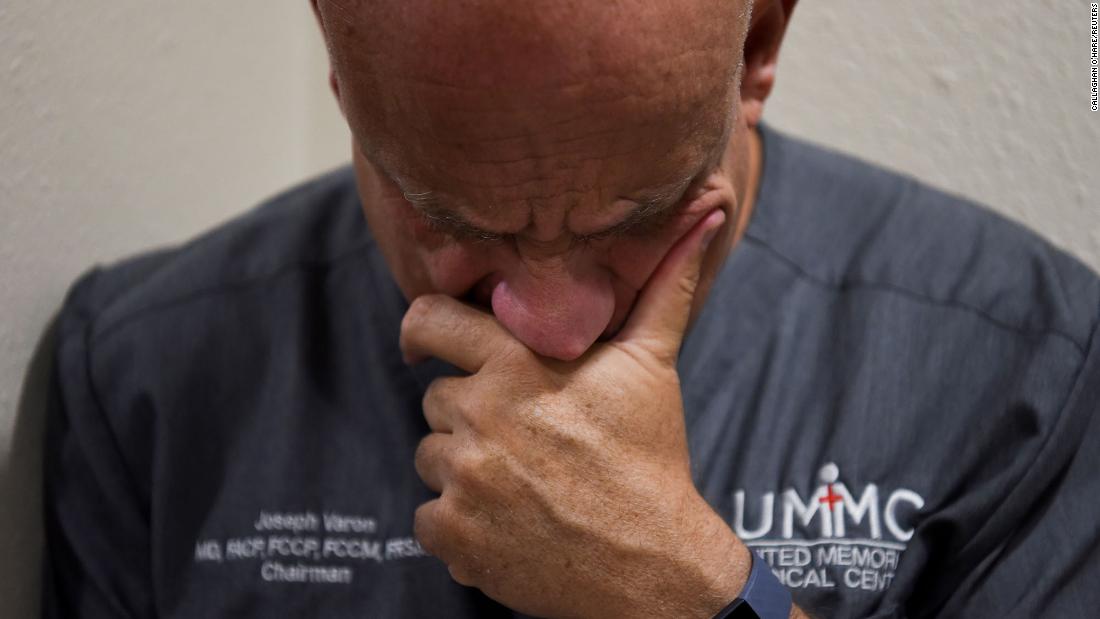

Friday was Dr. Joseph Varon’s 134th consecutive day leading the coronavirus unit at Houston’s United Memorial Medical Center

Dr. Joseph Varon, the chief medical officer at Houston’s United Memorial Medical Center, gets home after a long day at work.

Dr. Joseph Varon hasn’t had a day off in months.

Friday was his 134th consecutive day leading the coronavirus unit at Houston’s United Memorial Medical Center.

“If you ask me how the hell have I been able to survive for 134 days nonstop, I guess it’s adrenaline,” he said. “But I’m running on fumes. It’s tough.”

And last week was his toughest yet. With Houston dealing with a surge in Covid-19 cases, he signed more death certificates than he has at any point in his career.

“People were dying every day,” he said.

Nurse Flor Trevino prepares a body to be transported to a morgue. The patient died during an intubation procedure.

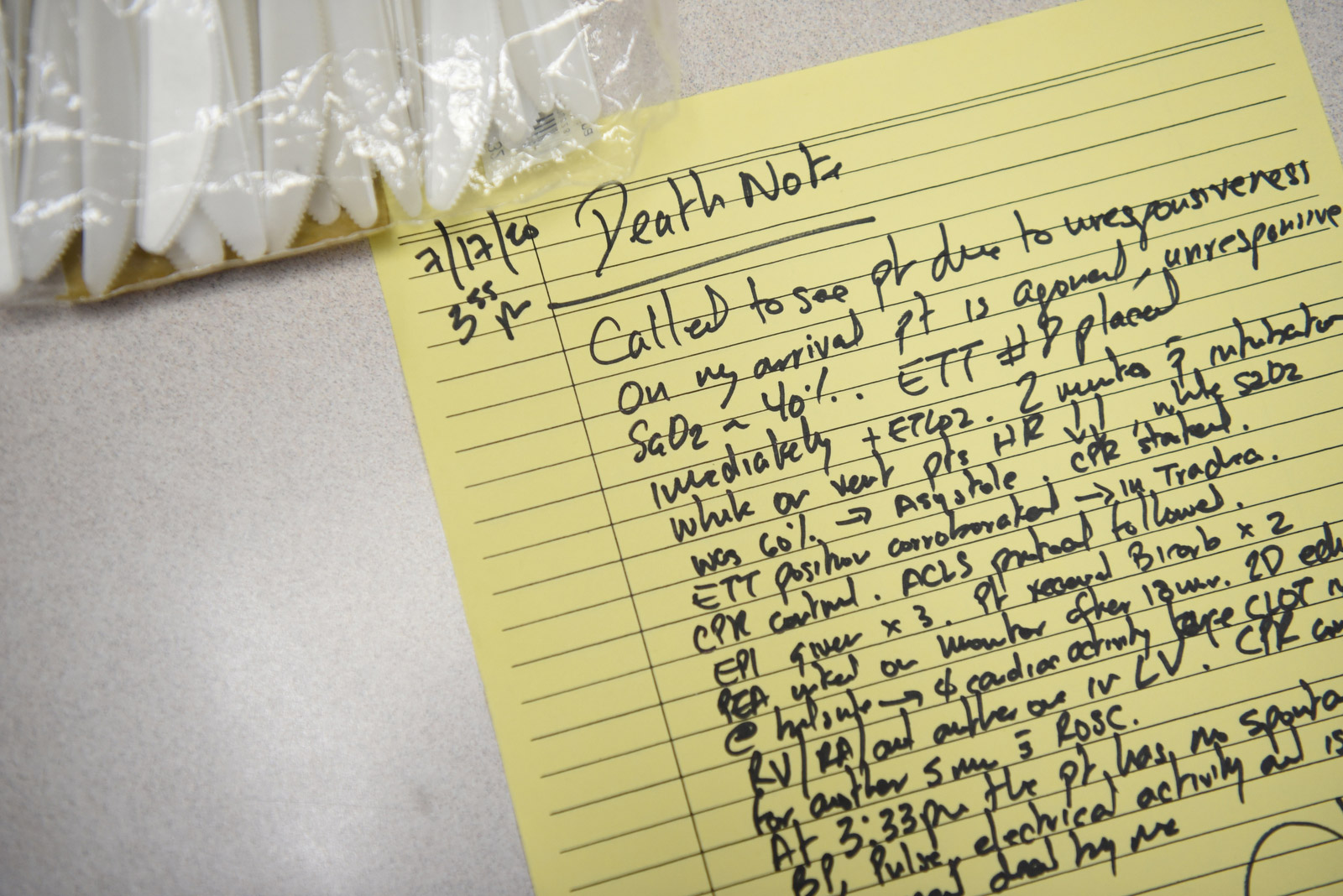

Varon wrote this note that detailed a patient’s death on July 17.

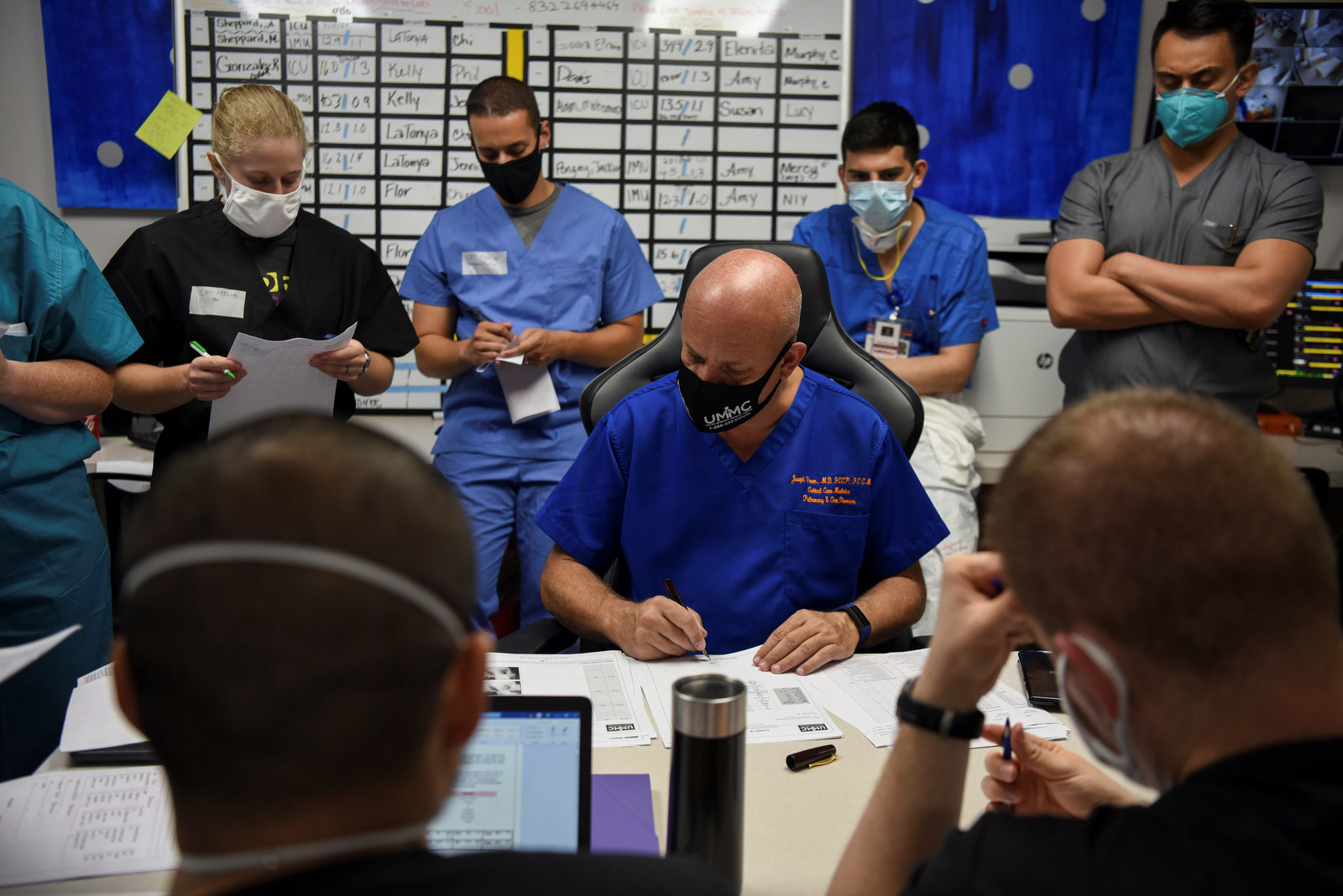

Varon’s workday starts early. Around 4:30 or 5 a.m., he heads to the hospital and goes straight to the coronavirus unit where he and his team go over each patient’s case.

Then he starts making the rounds.

“He’s involved with everything and very, very personal,” said photographer Callaghan O’Hare, who shadowed him several times over the past month. “He will sit on the bed with people and give them hugs and have a chat. It’s pretty incredible to watch.”

Caring for the coronavirus patients takes a minimum of 10 hours each day, Varon said. After that, he meets with his other patients in the hospital — the ones who don’t have coronavirus.

“If I am lucky, I get home before 10 o’clock at night. If I’m not lucky, which is most of the time, I make it home around midnight,” he said.

Varon and his team go over patient files during a daily meeting. “I’m afraid that at some point in time I’m going have to make some very serious decisions,” Varon said in July. “I’m starting to get the idea that I cannot save everybody.”

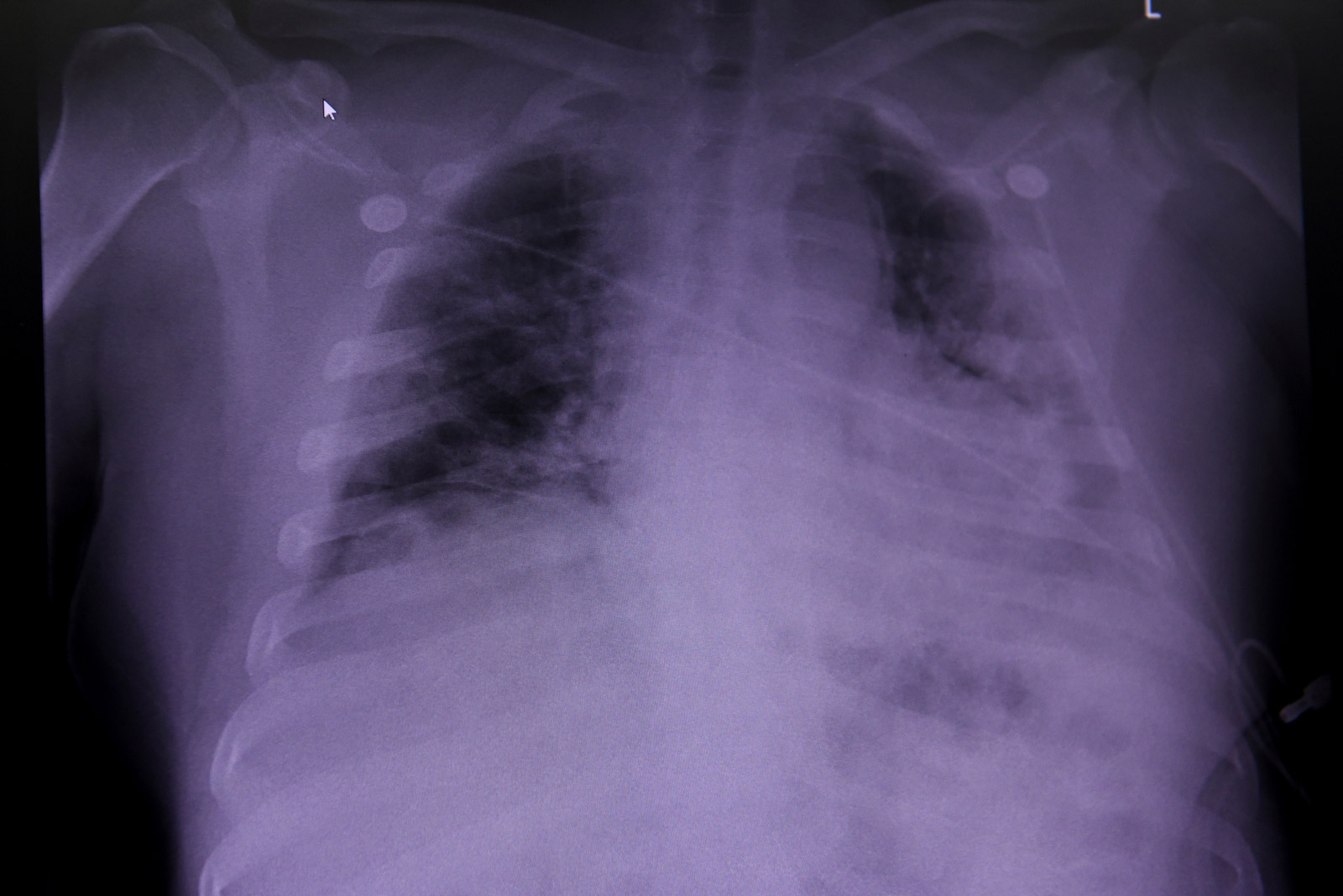

This X-ray shows a patient’s lungs inside the coronavirus unit.

Of course, Varon isn’t the only one making sacrifices. He is quick to praise his team and the long, hard hours they put in.

“The nursing life inside a Covid unit is tough,” he said. “Every time they go in and they wear those spacesuits, they come out sweating like there’s no tomorrow. It’s like a mini sauna for them.”

The work is physically exhausting, with everyone on staff wearing several layers of personal protective equipment, or PPE. Varon has seen nurses slip on their own sweat.

It’s also emotionally draining.

“I have seen nurses, in the middle of rounds, just start crying,” Varon said. “Crying because they just can’t handle it anymore.”

Varon passes a piece of paper to colleague Cesar Barrera as he checks on patients in the emergency room.

Varon talks on the phone while sitting at a table in the staff lounge. His phones — he carries two — are constantly ringing, and he’s often taking media requests and letting journalists get a firsthand look at what it’s like inside his hospital.

O’Hare says she was struck, however, by the resilience of Varon’s staffers and how committed they were to make a difference.

“They really try to take the time to get to know the patients,” she said.

It isn’t easy to connect with someone when your face is covered by a mask and a shield and you’re dressed head to toe in PPE. But Varon’s team has a solution.

“The doctor and then the nurses will all wear printed photographs of themselves over their PPE so the patients can at least know what they look like and have an idea of who they’re talking to,” O’Hare said.

Varon speaks to coronavirus patient Henry Rodriguez on July 10. The staff wears printed photographs of themselves so that they can make a more personal connection.

Efrain Guevara lies on a hospital bed on July 17. He was hospitalized after being diagnosed with Covid-19.

Three nurses on Varon’s staff have contracted Covid-19 in the past few months. Varon doesn’t know where they contracted it, but at the hospital they’re always careful with regards to PPE.

“I often tell people I feel more comfortable inside my unit than outside my unit,” he said.

Nurse Christina Mathers tested positive last week.

“That’s the hardest thing to ever hear. … It messes with you,” said Mathers, who had been working every other day since April 29. “But I wouldn’t go anywhere else but here.”

Varon hugs Christina Mathers, a nurse from his team who became infected with Covid-19.

A worker places a sign reading “cleaned vent” onto a piece of medical equipment.

Houston is the county seat of Harris County, which as of Friday was fifth in the United States for most confirmed cases of Covid-19.

“I’ve heard quite an increase in ambulances, just at all hours of the day,” said O’Hare, who lives in Houston. “And I’ve done quite a bit of coverage standing in the parking lot of the Texas Medical Center and seeing the number of ambulances going in and out at testing facilities.“

She says she’s seen people show up at 11:30 the night before just to be sure they have a spot in line and can get tested the next day.

“It’s pretty chaotic,” she said.

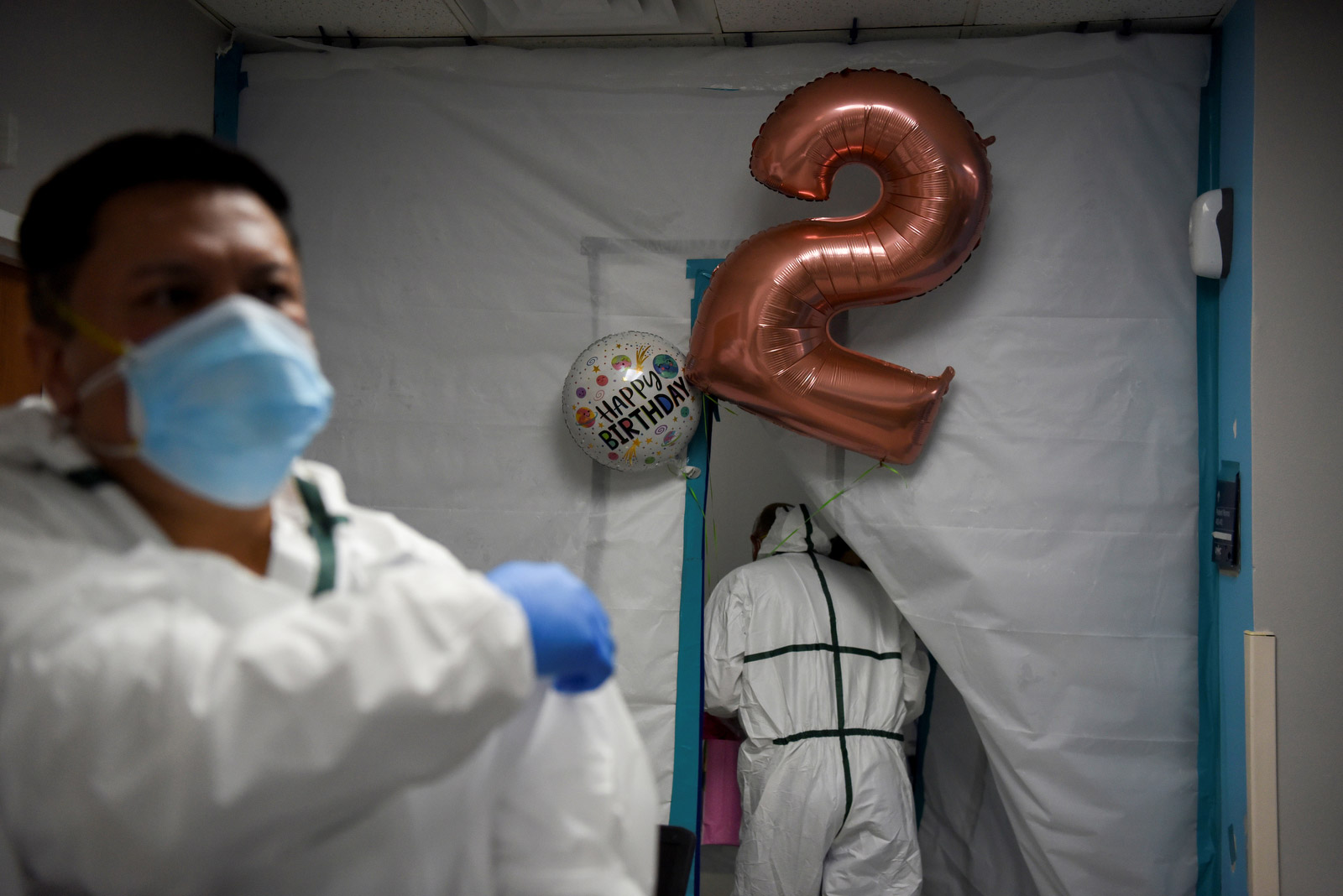

A man delivers balloons to the room of a coronavirus patient who was missing his daughter’s birthday.

A medical student checks on Larissa Raudales, an 18-year-old who was hospitalized after being diagnosed with coronavirus. “I was terrified. … I thought I couldn’t breathe anymore,” Raudales said. “I just thought I was going to practically die right there.”

The first two times O’Hare visited Varon’s hospital, the coronavirus unit was at maximum capacity. The US Army came later to help expand the area and add more beds.

Some of the people O’Hare saw during those earlier visits didn’t survive. It was tough to think about.

“One of the hardest things to watch was after a man died, they put his belongings in a plastic bag next to him — just basketball shorts, a T-shirt, shoes,” she said. “And it really struck me that this man died without his family and friends being there to say goodbye.

“No one deserves anything like that, and we all have a part to play in making sure that that doesn’t happen to more people in Texas.”

Jonnie Harrison sleeps in a bed next to her husband, Riley, on July 25. Both of them were hospitalized in the coronavirus unit.

Health-care workers take a break from treating coronavirus patients.

Varon has been outspoken about the Covid-19 threat and the importance of wearing masks. That hasn’t sat well with everyone.

“People are calling my office and leaving threats because of all the media I’ve been doing, because they don’t believe that what we’re doing is real,” he said.

Varon wants people to see: This is not a hoax. This is a real thing. People are dying.

“You have no idea my frustration when I leave the hospital, I’m heading home, and then in one of these outdoor malls I see a hundred cars, a bunch of young guys or young women having a party — no face masks, no nothing. That kills me,” he said. “People are not listening.”

A medical-school student takes a nap in a break room. The team has been working around the clock this past month to deal with a surge of Covid-19 cases.

Callaghan O’Hare is a photographer based in Houston. Follow her on Instagram.

Photo editor: Brett Roegiers

![]()